"The colonial bungalow, identified by its extensive perimeter verandahs, dominant hipped roof, and low-slung horizontal form would have been familiar to any British colonist who had spent time in India or the Pacific possessions where it had become the standard expatriate house type."

Martin Segger, The Buildings of Samuel Maclure

|

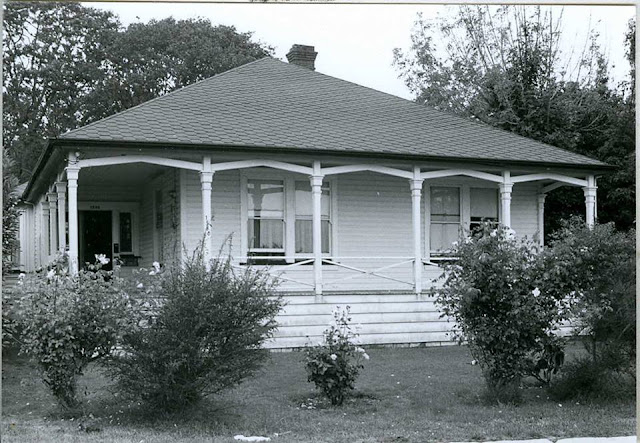

| A tasteful colonial bungalow with drop siding, classical details, chamfered posts |

Victoria's ongoing love affair with the house-type known as the colonial bungalow began early in the city's history, not long after the original Hudson's Bay Company fort (built in 1843) morphed into the Colony of Vancouver Island (1849) and the city-proper emerged from nowhere in response to gold's discovery in the Fraser Valley in 1857. The discovery of gold on the Fraser also instigated creation of the Colony of British Columbia, to better safeguard British claims to the territory against the expected onrush of prospectors, many of whom were Americans. If the ensuing gold rush caused Victoria's population to swell quickly as thousands of miners outfitted and provisioned themselves here, new business opportunities were afforded to merchants purveying goods and supplies. Within this dynamic of sudden growth and newfound wealth an architectural form appeared that would have been familiar to any residents of British imperial background, taking the shape of the hipped roof and other characteristics associated with the Anglo-Indian bungalow. As the opening quote suggests, this colonial-type bungalow would have been recognizable to anyone who had lived previously in a British Pacific colony. Bungalows like these were low-lying, single storey affairs, often with somewhat over-scaled roofs, and typically equipped with verandahs that gave them a distinctive look. This sort of bungalow first emerged in India, where a rural Bengali house-type was adapted to meet the needs and expectations of Britain's colonial administrators and military brass. Curiously shaped versions of a relatively obscure native dwelling-type (the chauyari, according to Michael Kluckner, originally with a pyramidal roof of thatched material), they eventually leapt in much-modified form from India to Britain's other Pacific colonies, arriving in Australia early in the nineteenth century. The oldest surviving example there, Elizabeth Farm, shows the distinctive look of an Anglo-Indian bungalow, and dates to the early 1800s. It remains celebrated today as an exemplar of colonial housing in early Australia, influenced directly by the British experience in India and likely prompted by the presence of military figures who had served in India in the newfound colony.

This same characteristic hipped roof also appeared unexpectedly in the burgeoning Colony of Vancouver Island, embodied in the features defining the look of the colony's first legislative buildings, which were begun in 1859. Its appearance in Victoria is perhaps unsurprising in light of the British fascination with the bungalow's unique mix of exotic and practical features, or the desire of the colony's governors to establish it as a British possession. Victoria quickly became home to many professionals of British origin, attracted to the colony by the opportunity to prosper if possessing the right types of skills. These surveyor-engineer-architect types would also be joined by other expatriates, such as retired colonial administrators or military men, who were drawn to a colonial outpost by the prospects of genteel living in a paradisial spot. All of which added up, over time, to there being a receptive local audience for architectural versions of this imported, exotic building type. The following essay examines the influence of three local architects whose professional work involved designs for specific clients that helped indigenize the colonial bungalow-form in these parts - the first of these clients being the Colony of Vancouver Island itself, headquartered in what became the City of Victoria in 1862.

1. Herman Otto Tiedemann

|

| Hip-roofed administrative buildings designed by H.O. Tiedemann, circa 1866 |

|

| View across James Bay to the bungalow-roofed legislative cluster, circa 1874 |

Early indications of the colonial bungalow enjoying cachet in Victoria took the form of the distinctive hipped roofs that capped the colony's first cluster of legislative buildings (pictured above), known formally as the Colonial Administration Buildings. This grouping, designed by German-trained architect and engineer H. O. Tiedemann, was constructed beginning in 1858, the year that word of gold's discovery on the Fraser River began enticing hordes of would-be miners from around the globe to these parts. Financed with monies derived from the astute sale of suddenly valuable downtown lands (orchestrated by the colony's first governor, James Douglas) the new buildings were intended to tie the future legislative assembly more closely to the evolving city by bridging the mudflats of James Bay (coincidentally providing Douglas himself with a more direct route to his home on the far side of the bay). There is an element of conjuring about this early civic cluster, appearing as it did just in time to transmit a sense of settled authority governing the territory (to some extent this was defensive sleight of hand). But what seems truly curious here is that an architect who trained outside the British imperial tradition would wind up adopting colonial bungalow features as the integrating element for his designs. The resulting 'curious' confections, likened by the Victoria Gazette to "Italian-villa fancy birdcages", were initially given a rather rough ride for their eclecticism (sitting poorly, for example, with the clamorous Amor de Cosmos, a future Premier of British Columbia, then a journalist, who dismissed them contemptuously as "something between a Dutch toy and a Chinese pagoda").

And yet, over time, the Birdcages (as they came to be popularly known) would be regarded more fondly by the general public, perhaps as maturing grounds elevated their quaint charm in the dramatic setting of Victoria's inner harbour, with its picturesque mountain and ocean backdrop. Architectural historian Martin Segger, in his masterful The Buildings of Samuel Maclure (In Search Of Appropriate Form) takes these distinctively hipped roofs and other bungalow features (placement on a low podium set close to the ground plane, furnished with ample verandahs) as indicating an underlying resonance of the colonial bungalow building form. This should not surprise us in what was, at the professional level at least, a very British colony. One distinctive feature of the Tiedemann designs was the manner in which he lifted his hipped roofs by breaking and raising the tail of the rafters. Architecturally, this extra lift along the hip rafters enables the roof to be run further out over the building's walls, emphasizing its sheltering quality while accommodating the verandahs that are typically tucked under it. The lifting of the roof-line was an early instance of a feature that would ultimately become definitional for the building as widely constructed around Victoria: a distinctively bell-cast hip roof. What happened over time was that this original defining lift in the roof angle migrated further and further down the hip rafter. Lifting the tail of a hip roof was common in historic instances of this building type as it came to be built outside of India (cf inset photo below right of Elizabeth Farm in New South Wales, Australia, where the hip roof has a distinct uplift (or 'broken pitch' in Australian parlance) as it descends from the ridge line.

|

| Early Australian colonial bungalow with bell-cast roof |

But this was not always and everywhere the case. Colonial bungalows could also be designed without any such lift to the hip rafter, a choice of treatment that reflected more faithfully the native Indian practice of using thatch as a roofing material, piled deep in order to repel monsoon rains - resulting in both an amplification of roof volume and a most singular look. Forty years on, Tiedemann's choice of a lift in his hip roof would be echoed (if rather more gracefully) by domestic architect Samuel Maclure. Alternatively, John Gerhard Tiarks, another local designer of colonial bungalows who worked in the late 1890s, preferred hip rafters with an unbroken pitch, leading to a different overall effect. Ultimately, the dominant trend locally was to adopt a lifted hip, flared near the eaves so as to project more boldly over the walls. But Tiedemann certainly started things rolling with his eclectic designs for the colony's first administration buildings. A number of authors see this representation of the colonial bungalow roof-line as a more-or-less conscious shaping of space to be recognizable to British eyes, especially for those with colonial experience elsewhere.

|

| Hipped roofs, lifted well out over the walls, give a sheltering look to these bungalows |

Other authors writing about the Birdcages also recognize the colonial bungalow's familiarity of shape to, and underlying popularity with, the initially small audience of expatriate Brits that comprised Victoria's professional class. As one example of this, a brochure entitled Discover Your Legislature, published by the office of The Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, situates the building cluster as follows: "Tiedemann took his inspiration for the Birdcages from a 'colonial bungalow' design that originated out of British-occupied India and combined it with European influences, such as those mentioned in the newspapers as being stylized after a Swiss-cottage and Italian-villa..."

|

| Some of the Birdcages persisted after Rattenbury's stone replacement arrived |

Robert Ratcliffe Taylor, author of a recent history of the process of building the Birdcages and of the momentous legislative choices eventually made within their precincts, reinforces the idea that the colonial bungalow was recognizable to Victorians with prior experience of the India-Pacific region. In a recent essay in the Ormsby Review ( well worth

| |

| Fort Victoria in 1861: "close ties"? |

absorbing) entitled "The Mysterious and Difficult Hermann Otto Tiedemann," Taylor suggests that the legislative cluster's "hipped, bell-cast roofs, projecting eaves and fretted vergeboards did indeed give them an unusual, almost 'Oriental' appearance... Moreover, their ground-hugging, wide-verandahed appearance echoed the bungalows of British India, which already had close ties with Victoria." Consider the inset photo (right, above) showing Fort Victoria as seen from Wharf Street in 1861, for one indication of a possible source of such early 'close ties' with Victoria.

|

| With landscape now maturing, the Birdcages relax more in their striking setting |

2. John Gerhard Tiarks

While it would be fascinating to know more about the colonial bungalow's history during the era of the Birdcages (roughly 1859 - 1898), what is known with certainty is that, from the late 1890s on (with a return to booming economic conditions and more-sustained population growth) there was a definite market for architect-designed variants of the colonial bungalow house-type, for use as year-round residences. The remarkable, if lamentably brief, career of architect John Gerhard Tiarks (who died suddenly after falling from a bicycle in 1901, at 34) demonstrates this in spades. The British-trained Tiarks moved to Victoria in 1888, where he enjoyed immediate success designing residences, often executing his projects 'on spec' (meaning, building them on land he had purchased, using his own designs, overseeing their construction, and then selling them to willing buyers - an early version of what would become known as 'the housing market'). Despite a career lasting a mere 13 years, Tiarks was busy designing over 75 buildings in the Victoria area! Later on, he launched himself further into residential real estate, partnering with rising star Francis Mawson Rattenbury on the purchase of some prime acreage in then-relatively undeveloped Oak Bay. These attractive holdings were once part of what was then known as the Pemberton estate (J. D. Pemberton was Crown Surveyor of the colony, having worked previously for the Hudson's Bay Company from 1851; he was a talented man, part explorer and part skilled mapper, who laid out the townsite for the City of Victoria and the suburb of James Bay, so positioned himself to get in on the ground floor in local real estate). A portion of the 15 acres of land acquired by the duo came with ocean shoreline, which went to Rattenbury for the purpose of building his family home (Lechinihl - today part of Glenlyon Norfolk school); other parts were developed and marketed in parcels with estate-like design controls. In 1898, Tiarks created a remarkable colonial bungalow at 1512 Beach Drive on a parcel of these lands, for Arthur and Matilda Haynes, which still stands today. This classy early colonial bungalow has many of the features that we see reappearing as standard treatments in the more-popular but later California bungalow era.

|

| Sophisticated verandah with a separate roof form fronts this 1898 version |

|

| A stone foundation with low railings impart rustic informality to this house |

In

what was his signature treatment, Tiarks chose not to lift the

edges on his hipped roofs, preferring instead a long, straight rafter line that emphasized roof volume. As noted above, this roof treatment was closer to the Anglo-Indian bungalow as it was widely built in India (see inset photo, below right, of a bungalow in India with a thatched hip roof for the general idea). Interestingly, even at this early date, Tiarks is setting dormers into the house's roof in order to achieve modest spatial gains (thereby anticipating the California bungalow's tendency to exploit the attic space while avoiding the effect of creating a full two-storey house). Also, at the Haynes house above, he gives the verandah a separate roof, which is projected at a less steep angle than the main roof (so imparts a sense of lift). Eastholme (photo below) was another Tiarks' design, at 1580 Beach Drive in Oak Bay, this time

|

| Englishman's bungalow: note classic thatch roof |

for Herbert F. Hewett, built in 1899. The building continued here until 1992, when it was relocated to Salt Spring Island in order to make way for the more grandiose offering now gracing its site. Eastholme is a somewhat plainer and less-complicated affair than the Haynes bungalow, as shown by the absence of dormers in its roof and by the more economic recessing of the verandah entryway under the principal roof form. It was nevertheless another example of an early colonial bungalow-form in Victoria, with definite cottage-like charm (again, consider the similarities with the inset photo to the right above, from LIFE magazine, pre-1947).

|

| Eastholme, designed for H. F. Hewett (1899), now removed to Saltspring Island |

Tiarks also designed a pair of enormous colonial bungalows in 1898 (seven thousand-plus square feet each!) situated on some prestigious holdings off York Place in Oak Bay, for a pair of well-heeled solicitors who were partners in a Victoria law firm. Both had previously sampled high office in successful political careers in other parts of the country. One of these twin bungalows, named Annandale (inset, below right), was built for Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper, once a Justice Minister in the Dominion government and a relative of Sir Charles Tupper, who was one of the fathers of Confederation; the other bungalow, known as Garrison House, was built for the Honourable Frederick Peters, a former Premier and Attorney-general for Prince Edward

|

| Annandale and Garrison House, shown shortly after construction in 1898 |

A few observations on Tiarks' styling of these gigantic colonial bungalows: a sharply rising hip roof architecturally that dramatizes the roof's volume was evidently his design preference. This suggests that Tiarks' interpretations of the colonial bungalow did not factor into the standard form it ultimately took (ie., the one most widely built in its construction heyday, which typically delivered it with a bell-cast roof-line and dormers styled to echo the main roof form). Tiarks also intended the verandahs on these buildings to have a significant presence, as he made them into a central feature defining their look by wrapping them along three sides of the buildings. Here they effect a transition between building and surroundings, capturing views of environmental features from within a substantial space that's sheltered from inclement elements. Verandahs were entirely practical in Victoria's unusual wet-dry climate (with its wet fall and winter) building on their traditional use in the Anglo-Indian bungalow where they provided relief from both intense heat and heavy seasonal rains. Another function they serve, also arising from lived experience in India, was their potential for use as a social mixing space in what comprised in effect a sequence of roofed outdoor rooms. This transitional zone adds a certain exoticism to the overall bungalow experience, lending a sense of informality to a novel physical space that simultaneously provides a sheltered entry to the residence. Tiarks clearly intends these verandahs to play a key role in defining the overall look, once again tucking them under a separate roof form that is angled into the main roof plane.

|

| Annandale, circa 1959, still showing much of the original conception |

To my eye however, there are some residual Victorian elements to Tiarks' design of these bungalows, one example of which is the trio of contrasting dormers set into his massive hipped roofs. It's almost as if decorative variety were his goal rather than the arts-and-crafts objective of achieving a more integrated outcome. Looking at photo two of Annandale (above) we observe that each dormer is treated entirely differently from its mates: the largest of the three (furthest to the right) sports a gable roof with its tips buried within the main roof; notionally it seems in sync with the dominant roof form, yet somehow it is not quite, to my eye at least, an architectural synthesis. By contrast, the middle dormer is a long, narrow, shed-roofed affair, terminating in two relatively small windows. To me, this dormer feels somewhat dwarfed by the vast expanse of roof it springs from. Sharpening this contrast even further, the third dormer (to the left), is also gable-roofed but this time with tips exposed and the gable decorated, contributing to a confusion of shapes and treatments that lack any inherent relationship to one another.

|

| The Weiler brothers' colonial bungalow: an exclusive rental with stunning views |

Tiarks' designs may not have anticipated the ultimate form colonial bungalows would take locally, but his success as an architect with an interest in this idiom reinforces the notion that there was underlying demand for this precise look of house in Victoria at the turn of the twentieth century. The colonial bungalow appealed broadly to individuals of British extraction: from mustered-out colonial administrators seeking quiet enjoyment of a peaceful setting, to retired officers looking for the trappings of wealth at a good price, it included an emergent group of successful local business and professional families who aspired to own a residence that expressed status, modernity, and a definite connection to the glories of empire. Buildings such as these might be custom-designed for specific well-heeled clients (like the York Place couplet or the singletons on Beach Drive) but they could also be designed 'on spec' for the market or custom-built for investors looking to offer rental accommodation that might attract a moderately well-heeled demographic who wanted access to safe, temperate Victoria. The city was, after all, by this point successfully marketing itself as a tourism

3. Samuel Maclure

A further indication of ongoing local demand for this specialized building type is revealed in the practice of residential architect Samuel Maclure, who created a stream of innovative colonial bungalow designs that proved highly popular in Victoria. In 1899, Maclure declared his interest in the medium by designing a novel colonial bungalow to house his own family, located on Superior Street (COV Archives photo, above) just around the corner from Rattenbury's new Legislative Assembly building. Immediately popular in Victoria (Segger calls it "an instant success") this noteworthy reworking of the house-type would serve as a 'calling card' for Maclure's new professional practice. The architect's reputation was further amplified when publications like Victoria Homes (a local newspaper feature aimed, in part, at tourists) repeatedly ran pictures of it as proof of the underlying vitality of local architecture. This newfound notoriety led to additional commissions for similar structures, which in some instances were fairly literal reprises of the original building. Over the ensuing years, however, Maclure continued to evolve his approach to the colonial bungalow form, varying his treatments in order to demonstrate design-originality. Maclure's family home ("a gracefully understated design") and the followup colonial bungalows also furnished local contractors with models that any number were quick to copy, building their own 'interpretations' for a rapidly expanding housing market (and equally typically, losing some of the Maclure finesse along the way). In this manner, Maclure's early innovations may have played a formative role in achieving what became the building's paradigmatic form.

Segger offers the following on Maclure's approach to the styling of domestic architecture: "Specializing in small house design Maclure was also searching for a distinctive personal style with a uniquely regional flavour....Maclure's immediate inspiration was local. Drawing on the most prestigious standing structures (the Georgian style HBC [Hudson's Bay Company] buildings and colonial bungalow forms of the old government buildings the 'Birdcages') he quickly forged a highly original residential type. The meticulously designed but rather unostentatious hipped-roof and shingle-clad bungalows became a familiar part of the urban landscape." Segger also notes that Maclure's family home galvanized demand for buildings of this type: "revolutionary but traditional, its startling fresh design was to be the prototype for a long line of smaller houses wherein even replicas of the architect's were both demanded and occasionally supplied with few modifications."

A good example of this pulse in demand for structures on this new model of colonial bungalow is Arden (pictured below, COV Archives) erected at 1176 Beach Drive in 1902, for Ada and Hugo Beaven (son of former BC Premier Robert Beaven). This very handsomely detailed colonial bungalow was unfortunately demolished, a fate that sadly also befell the Maclure family bungalow.

|

| Arden surrounded by mature landscaping - a fixture on Beach Drive (ca 1930) |

Indeed, so popular were these new colonial bungalows that local builders and architects were keenly interested in supplying their own versions of what they called 'the Maclure bungalow'. These early examples of Maclure's handiwork developed new expectations of what could be done with a modest but artistic, cozy yet fully modern home. Among Arden's outstanding features is its finely proportioned hip roof, gracefully flared near the edges, rendering it in an elegantly bell-cast shape that emphasizes sheltering effect and stylishness (all features that would come to typify the mature form of the building). Also noteworthy is the recessed entry verandah, a frequent Maclure feature, providing shelter from the elements and adding to the overall feeling of coziness and stylistic elegance. Another fine feature is the proportioning and placement of the front dormer, which floats decoratively in the main roof space, echoing the bell-cast hip of the main roof form. There is also a conservatory-style pavilion to the left, advancing into the maturely landscaped setting while sitting securely under its own stylish hipped roof. Here at Arden, the garden conservatory functions as a windowed sun room, while at the Maclure family home it manifested as a true verandah, which while roofed is otherwise open to the elements. Arden, like the Maclure family home, is a resoundingly horizontal building (befitting a bungalow in an outer suburban, then-country setting) set close enough to the ground plane to emphasize those qualities. This sharpens the contrast with the more vertical Victorian-era houses typical of the more closely packed inner suburbs nestled against Victoria's downtown. There is also little of the tacked-on ornament characteristic of so many Queen Anne-style houses of the high Victorian era (although, if you look closely, Maclure's personal enthusiasm for finials is evident). In those days, arts-and-crafts architects studiously avoided the Victorian embrace of architectural doodads, preferring instead to emphasize features like local materials for wall texture, decorative expression of the building's structure, and above all, refined proportioning of the building's masses. Arden is a colonial bungalow built in an emerging and pretty suburb that remains rural, with gardened grounds fringed by a mature treed landscape - the building feels nestled-into its surroundings, in a comfortable manner, crowning its slight rise.

|

| 132 Dallas Road, ca 1974, a contractor's version of the Maclure bungalow |

The photo above shows what is likely a builder's version of 'the Maclure bungalow' (COV Archives). Signs that this wasn't Maclure's own handiwork include the building's stucco exterior, the over-steep and concreted front steps (Maclure preferred wooden steps and landings in a graceful sequence), a general coarsening of building features in order presumably to keep the costs down, and a telling absence of finials (a Maclure hallmark)! While there was demand for any number of such builder versions of Maclure's radically restyled colonial bungalow, there was also plenty of demand for the real article too - and even a little from out-of-country, in at least one area of the Pacific Northwest that we know about. An example of this is the Ramsay House (insert, right, above) constructed in Ellensburg, Washington in 1905, for a wealthy couple who had recognized Maclure's artistic talents while vacationing in Victoria; able to review samples of his work firsthand, they convinced themselves he simply had to become the architect of their family home. The Ramseys commissioned him to design a unique variant of his colonial bungalow, which here presents an early instance of Maclure deploying a straightened version of the hip roof, without a perceptible lift at the edges (a feature repeated for the roof on the front dormer). And while a conservatory bay projects into the garden at the left of the photo, in this instance a second, and preponderant wing, runs perpendicular to the first, thus expanding the home's footprint while enabling an elaborate recessed entry verandah.

The photo above shows what is likely a builder's version of 'the Maclure bungalow' (COV Archives). Signs that this wasn't Maclure's own handiwork include the building's stucco exterior, the over-steep and concreted front steps (Maclure preferred wooden steps and landings in a graceful sequence), a general coarsening of building features in order presumably to keep the costs down, and a telling absence of finials (a Maclure hallmark)! While there was demand for any number of such builder versions of Maclure's radically restyled colonial bungalow, there was also plenty of demand for the real article too - and even a little from out-of-country, in at least one area of the Pacific Northwest that we know about. An example of this is the Ramsay House (insert, right, above) constructed in Ellensburg, Washington in 1905, for a wealthy couple who had recognized Maclure's artistic talents while vacationing in Victoria; able to review samples of his work firsthand, they convinced themselves he simply had to become the architect of their family home. The Ramseys commissioned him to design a unique variant of his colonial bungalow, which here presents an early instance of Maclure deploying a straightened version of the hip roof, without a perceptible lift at the edges (a feature repeated for the roof on the front dormer). And while a conservatory bay projects into the garden at the left of the photo, in this instance a second, and preponderant wing, runs perpendicular to the first, thus expanding the home's footprint while enabling an elaborate recessed entry verandah.

|

| Gore house (1912) was a remarkable innovation in bungalow design |

Looking at Maclure's buildings today, one has the impression that he relished the act of refining their shape and detailing, whether they were grandiose or compact, and that this almost playful trait in the architect somewhat accounts for the sheer variety of his essays in the colonial bungalow style over three decades. By 1912, when he came to design Gore House at Regent's Place (photo above, with a now regrettably anodyne colour scheme) his conception had evolved considerably from that organizing his family home in 1899. Gore House is set across a gently sloping landscape, on foundations so low the building appears to rise directly from the land itself, in California arts-and-crafts style (see photo, above). The exposed rafter tails under its projecting hip roof give this bungalow somewhat of a Craftsman touch (yet it does come equipped with gutters and downspouts, which are a practical necessity in Victoria's rainy winter). But in this instance Maclure's dormers have become flat-roofed, standing in sharpened contrast to the bell-cast main roofline, and are significantly larger in size so as to optimize the interior spatial gain. The heightened hip roof also serves this end. One is tempted to say that Maclure, a talented artist, is evolving his conception of the colonial bungalow away from the builders' stereotypical version of it.

|

| The main roof-form is subtly bell-cast and the roofed entrance mimics its form |

There is also a projecting roofed-over entryway that traces the main roof's form, both being gently lifted at the edges (photo above). Segger says that Maclure continually modified these interpretations so as to better meet the needs of his clients and the particular site he was designing for: "While builders and other architects were quick to follow with their own versions of the Maclure bungalow, the form remained with the architect a gradually evolving house-type to which he returned again and again, always with a variation which better adapted it to client, location and current taste."

|

| Dormer treatment and slight lift to the roof, which is now getting much steeper |

For the A.O. Campbell House (elevations above, UVic Library) also designed in 1912, Maclure retained the contrasting, flatter dormer roofs as at Gore House, but made the main hipped roof rise even more sharply, further dramatizing roof volume. The edges of his roof still flare gently outwards in what the eye sees as a delicate curve, near the edge of the rafter. The building pictured above also nestles comfortably into its rocky situation, sited near the ground plane in a way that leaves nature's original bequest as undisturbed as possible. This evolving Maclure style was by now quite familiar to local eyes, making his designs even more sought-after by the discerning subset of people who could afford an architect-designed home. Maclure's unique way of doing this, his architectural 'indigenization' of the colonial bungalow form, may in earlier days have contributed certain design-leads for the paradigmatic shape these buildings ultimately assumed as units of an expanding suburbia; but here we see him veering further away from any literal repetition of the form his buildings had taken. Segger says Maclure was always intrigued by the possibilities of the colonial bungalow form, tackling it anew over nearly three decades, and going so far as to explore its potential to be scaled-up grandly into a novel form of mansion-house. Nowadays these intriguing smaller buildings are occasionally referred to as 'Edwardian' bungalows, or even as 'Edwardian' cottages (muddying the waters further) but they are in fact 'colonial bungalows', despite sharing features like coziness with British cottages; they descend directly from colonial antecedents in India, so they are properly termed colonial bungalows. And besides, a market for this genre of building existed on either side of what was the Edwardian era (technically, a period from 1901 - 1910) so the colonial bungalow's story is in no way limited to, nor captured adequately by, the abbreviated compass of this notional era. Eventually a substantial number of bungalows following a more-or-less paradigmatic version of the principal program would be built, in every corner of the region, typically appearing in suburbs alongside other contemporary housing (originally often built in trios, by contractors, during the summer months, as buildings built on spec often were early in the twentieth century). They are likely the by-product of contractors directly cribbing treatments like those at Arden or the Maclure family home on Superior. I will have more to say about that phenomenon in part two of this article, but for now here's a quite lovely, if slightly incongruous, interpretation of the paradigmatic style (photo below). Note that despite the classical brackets and the stone foundation and piers, the verandah has shrunk here to a mere half-width of the frontage, while a diminished bay window (more a sidewall feature than a frontal bay) has been run out to its edge. While this instance has some very positive features to it, the loss of half of the verandah, making it more an entry-porch, renders the design discontinuous and somewhat incongruous. But it is still a beautiful building!

|

| Fairfield colonial bungalow: rustic flair from a stone basement and tapered piers |

A smaller part of the bumper crop of bungalows in this idiom erected from the late 1890s to around the start of the first World War were in fact architect-designed interpretations, styled expressly for clients who requested this type of house. But Maclure, however he may have contributed to the overall colonial bungalow design-trends with one or other of his early variants, was busily evolving novel versions for specific sites and clients. This dynamic can be glimpsed in the influences combining in the C. B. Jones house at 1911 Woodley Road in Saanich (1913, COV Archives, below). Designed for a successful Victoria contractor/engineer on the then-rural slopes of Mount Tolmie, for use as a luxury getaway, Maclure here opts for fully flat-roofed dormers but adds a really grand two-storey Tudor gable that relieves the huge roof form for a distinctive sense of entry. This time the now-steeply hipped roof has no apparent flare at the edges. Rafter tails are again visible, expressing part of the building's underlying structure in Craftsman fashion, and there are knee-braces securing the Tudored gable form, along with a dropped finial. Roof-wise, Maclure appears increasingly influenced by then-renowned Arts and Crafts designer C. F. A. Voysey, a British architect who also found colonial bungalow roof lines appealing (he often placed scaled-up hip roofs on the quite voluminous structures he designed for a relatively well-off clientele). Segger notes that from 1903 on "the low-rise hipped roof colonial bungalow undergoes a transformation into a larger roofed building of much more simplified form". The building pictured below appears also to have nascent corner buttresses too, another Voysey-like touch. The house itself is shingle-clad, after local arts and crafts fashion.

|

| Vacation house done for successful Victoria builder C.B. Jones in 1911 |

Whether or not we can discern any direct links between Maclure's early innovations and the paradigmatic form colonial bungalows took up until circa 1914 (when growth in general building around Victoria ground to a sudden halt) his design-vocabulary in this idiom continued to catch the attention of discerning people of means - those with the wherewithal to hire an architect to gain a really distinctive design. Maclure was very much in sync with the local market for this specialized building-type, his suite of designs comprising its leading edge. Maclure-designed bungalows might be modestly sized, as at Gore house, or they could be scaled-up substantially, like the Harry T. Shaw house on Foul Bay Road (elevation below, UVic Library). They might be built as year-round homes in town or as weekend houses placed in scenic locales for successful entrepreneurs. Segger says that the colonial bungalow "was well-suited to climates where combinations of oppressive heat and monsoon rain dictated open, well-ventilated but sheltered living spaces. Victoria's own mild, yet not always hospitable climate encouraged this kind of open, yet restricted, relationship with the landscape."

Despite the marked success of a more standardized (if still quite charming and comparatively well-planned) mass-market version of the colonial bungalow, Maclure continued tweaking his own designs in ways that ensured his buildings remained fresh and contemporary. One such bungalow - and a truly vast one at that - emerged in the form of Benvenuto (picture below) the garden home of Jenny and Robert Butchart (of Butchart Gardens fame) which Maclure evolved in a series of redesigns and additions between 1911 - 1925. Segger notes that we do not know definitively whether Maclure designed this house originally, but acknowledges that he may have. Intriguingly, the main bungalow incorporates many features closely associated with the paradigmatic form of these buildings, like the lifted edges of the large hipped roofs and the way the dormers echo that treatment. An undated photo (below, possibly from the thirties) shows Maclure's handiwork at the heart of a landscape that is much-appreciated by tourists and locals to this very day.

|

| Benvenuto, Butchart Gardens, massive structure shown circa the 1930s |

Maclure was also seasoned at deploying the hipped, bell-cast roof-form on his larger, multi-storey buildings. One occasion appeared early on in his career, in the form of the commission he won for Gabriola (1901/2), located in Vancouver's west end and designed for B.T. and Emily Rogers, owners of the ultra-successful B.C. Sugar concern. A prestigious endeavour for such a young architect (especially perhaps for one whose home base was little Victoria) Maclure showed he had the chops to design majestic residences for the well-heeled in surging Vancouver. This one occupied an entire city block when first built, incorporating gardens, outbuildings and a paddock for five horses. You can see from the picture below that the roof form (if far more grandiose and elaborated here than on any of his bungalows, due in part to the gravitas of slate as a roofing material) is nonetheless composed of elements similar to his early colonial bungalow roofs (see pictures below). Here the dormers reflect the proportioning and finish of the main hipped roof, floating gracefully in their allotted roof space. Maclure's comfort level with this elegant roof type is evident at Gabriola (which somehow has magically persisted to this day). Note how he forms his main roof (hipped, bell-cast, graceful) and how the dormers float in the roof space for optimal decorative effect.

|

| Gabriola, a mansion with colonial bungalow roof lines |

This luxurious building has classy touches galore, from its carved sandstone motifs (by John Wills Bruce, a Scottish architectural sculptor) and wooden classical detailing to its magnificent stained glass windows. Originally Gabriola sported much-more extensive grounds, placing it in a gardened landscape setting. And, apart from several insults inflicted due to conversion to a high-end steakhouse (the famous Hy's) plus a modicum of casual disfiguring of features through repurposing as suites, Gabriola itself remains substantially intact, a living example of Maclure's arts-and-crafts credo and period authenticity. Above all, it underscores his personal ability to realize a complete vision for a statement-house, working entirely through the hands of other artist-craftsmen. Gabriola has apparently now reverted to condo-suites, which may in fact comprise healthy recycling of this form of luxury heritage (especially if its ongoing maintenance is worked adequately into the homeowner bargain); sadly, the price of this rescue is that a brutally modernist piece of visual flotsam has been inflicted on the already abbreviated grounds. I'm both sad, yet at the same time glad, that it's being done - at least Maclure's artwork continues intact for future generations (and for a few lucky suite owners).

|

| Gabriola was named after the source of its sandstone exterior walls |

Whatever the commission, Maclure was disinclined to simply duplicate prior designs: each one represented fresh opportunity to shape a building, an approach that required a continuously evolving design-vocabulary. The Captain Verner house (picture below) dating to 1912 and built in Duncan, BC illustrates this continuous updating of Maclure's design-vocabulary in motion. This time we detect no lift at the edges of the roof, but again the dormers echo the main roof form. This time the walls sport prominent Tudor-boards (rather than the more subdued look of cedar shingles) in what seems a stark black-and-white contrast. Tudor detail and Tudor allusions were themes Maclure explored expressively on many of his buildings, viewing these touches as 'appropriate form' for a design-commissioning public of British background. Where the earlier use of cedar shingles as siding expressed west coast arts-and-crafts values, the demonstrative black and white scheme now emphasizes the British connection more fully.

|

| Blackened Tudor Boards point a sharp contrast with the white stucco panels |

Below is a picture of the E. D. Todd mansion in Oak Bay (Dainhurst), also designed in 1912, which saw Maclure scale up the colonial bungalow format in order to achieve a much grander building plan. Here a massive, two-and-a-half storey, Tudor gable frames a compelling front entrance, the verandah it leads through deeply recessed under the main roof form. The subtle bell-cast roof is back again in this example, dormers are of the firmly flat-roofed type, and the main hipped roof is absolutely gargantuan. The bungalow-form seems to invite this sort of exaggeration of features in the hands of creative architects, perhaps especially in the way the roof is treated in the instance of colonial-type bungalows. This mansion-version comes with rubble-stone foundations rising up into tapered stone piers that convey rustic flair and connect it to the landscape. In this example the Tudor boards are limited to the gable peaks and dormer sides and have been set in less-sharp contrast to the 'plaster' element, making them more understated in effect than at the Captain Verner house.

|

| The Todd mansion in Oak Bay saw Maclure scale up the colonial bungalow form |

It's

intriguing to consider that the colonial form of bungalow, while making the

rounds of Britain's Pacific colonies, came to have a life of its own in

a small community like Victoria. Here the colonial bungalow established itself as an indigenous type long before bungalows took off as subdivision housing in Los Angeles (a process that began about 1905). Los Angeles' success at using the bungalow-and-streetcar combination to extend suburban space would soon trigger the transfer of similarly-styled dwellings to

virtually every growing city-region in North America, eventually reaching as far afield as Australia. From Los Angeles the bungalow idea drifted northwards along the Pacific coast, setting up in growing urban regions where it was deployed to house newcomers attracted by prospering cities like San Francisco, Portland and Seattle. This transfer was propelled by the mounting wave of pattern books published by bungalow marketers like Jud Yoho or Henry Wilson, enthusiastic magazines like The Craftsman, and the ready availability of pre-cut models distributed from centres like Chicago via North America's abundant rail connections. Eventually, by about 1910, the California-style bungalow reached both Victoria and high-growth Vancouver, in the latter case taking off on lines similar to the LA development model. Victoria's bungalow constructors were active in the pulsing prewar period too (just not on anywhere near the same scale), while Vancouver enjoyed booming conditions and rapid population growth on both sides of the first World War. Victoria's architectural community was in one sense positioned to anticipate the entire

process of bungalow-extended subdivision, by dint both of the historic British

imperial connection to the bungalow-form and its early presence as a building type that initially met the expectations of people who could commission architects to design their homes. And local contractors extended this reach by copying or amending higher-style versions to create the beginnings of a mass market. Yet what a smaller city like Victoria (population around 46,000 in 1914) lacked to fuel full take-off was in-migration on the scale powering development in

neighbouring Vancouver. There, explosive port-and-railway-related growth translated more readily into sustained demand for speculative housing, fed by extensive electric streetcar networks, delivered in what were substantial subdivisions. The differing growth dynamics in these two centres meant that when bungalows caught on as mass-market housing in Victoria in the run-up to WW1, the colonial bungalow tended to be built as one of many bungalow-type options on offer to the broader public. While high-style demand for this building-form constituted a definite local market from the late 1890s at least, the mass market was served more by contractors than by architects, and as a result colonial bungalows went through the now-familiar process of cheapening, standardizing, and downsizing in their hands. This process did, however, make them more accessible to greater numbers of people, but over time popularity tended to come at the expense of quality, and as significantly, of size. The building shrank considerably to meet the needs of standardized lot sizes, often being dressed less elegantly in order to hold the line on price. Throughout the building's constructional heyday, a creative architect like Maclure might evolve his designs continually but the mass-market tended to run in the opposite direction, moving steadily towards greater standardization. And after WW1, Victoria's economy was in the doldrums right up until a second world war began to shake it loose.

So from about 1910 on, which saw the advent of the newly popular California-style designs appear in steadily growing subdivisions, Vancouver especially followed in the footsteps of bungalow promoters working in major U.S. cities. The effect was felt in Victoria as well, but to a far lesser degree. Indeed, the phenomenon of multiplying bungalow suburbias in both cities was widespread enough that Anthony King (The Bungalow: The Production Of A Global Culture) suggests that the two effectively comprised a kind of "California North". Certainly in Vancouver developers employed similar methods to those honed in LA: housing built in large tracts, using bungalow models that were differentiated sufficiently to maintain varied streetscapes, connecting suburbanites to jobs, services and entertainment with electric streetcars, and doing it all at relatively low prices due to cheap land and building materials. And by some strange alchemy, the colonial bungalow form that rendered itself paradigmatic in Victoria re-emerged as one of a half-dozen standardized bungalow types constituting the California type. So versions of it came to be built in subdivisions in many cities in North America (it was not, however, ever known as a colonial bungalow outside of BC, and it may or may not have enjoyed any relationship to Victoria's pattern). How this occurred is not something revealed by my research however, so the question of actual origins remains very much open. Nevertheless, as King notes, regional forms of bungalow design tended not to survive the tsunami of centrally generated patterns available in books, magazines and as high-quality pre-cut package kits for bungalow-style houses. To be sure, many high-style versions of colonial bungalows were designed for clients of means in Victoria (as there were for the California variant with its initial popularity here). But in a couple of decades at most, bungalows would become over-identified as cheap, accessible middle class housing, to the point where people of means consciously looked to other forms of building to express status and taste. So in the end, Victoria's colonial bungalow eventually fell to the same axe that killed the California variant. And when bungalows generally fell from favour (as they did with the onset of the Great Depression, if not sooner) so too the colonial bungalow largely vanished from view.

This is the first of a series of articles about the colonial bungalow's history in Victoria, B.C., a British Pacific colony where the building type was indigenized early in its history. Built here and there as one of a palette of expatriate design choices, it typically involved an architect who gave it a more-or-less distinctive appearance, before it enjoyed a second flowering in the era of mass-produced bungalow-types built on spec in subdivisions. Victoria's Colonial Bungalow Fling (2) explores the colonial bungalow in its heyday, both its architect-designed and builder-designed incarnations, including the era when the novel California bungalow was introduced and rapidly took over the new home market. In this era, with the notable exception of Maclure and other local arts-and-crafts architects who designed high-style variants, the colonial bungalow tended increasingly towards a set of repeating features in a distinctive style that soon became conventionalized. In this sense, the colonial bungalow was truly engulfed by the California bungalow's rapid overall popularity, and over time it became just one of the choices on offer within the larger bungalow phenomenon. There are still many fine colonial bungalows standing in our midst today, contrived back in the building's heyday; many more of them should enjoy formal heritage protection than currently do, so they are more likely to be retained long-term as community assets.

Books for looks:

The Buildings of Samuel Maclure, by Martin Segger (see especially Chapter Seven: Shingle Style and Colonial Bungalow, At the Confluence of Traditions)

The Bungalow: The Production Of A Global Culture, by Anthony D King.

Homeplace: The Making of the Canadian Dwelling Over Three Centuries, Peter Ennals and Deryck W. Holdsworth

Annandale Carriage House, Conservation Plan, Donald Luxton and Associates, November 2018, pdf available at oakbay.civicweb.net, providing a history of Tiarks' twin bungalows and an outline of his architectural career.

Notes from the Long Paddock, Michael Kluckner, available online at: https://www.michaelkluckner.com/longpaddock.html; a book-proposal by BC author MK on the history of architecture in Australia, illustrated by the author.

The Birdcages: British Columbia's first legislative buildings, 1859-1957, Robert Ratcliffe Taylor