"When both inside and outside work hand in hand, the result is a home that extends far beyond its actual walls." Sarah Susanka, Home By Design

|

| Small variations in wall planes extend a building into the landscape, helping unify both |

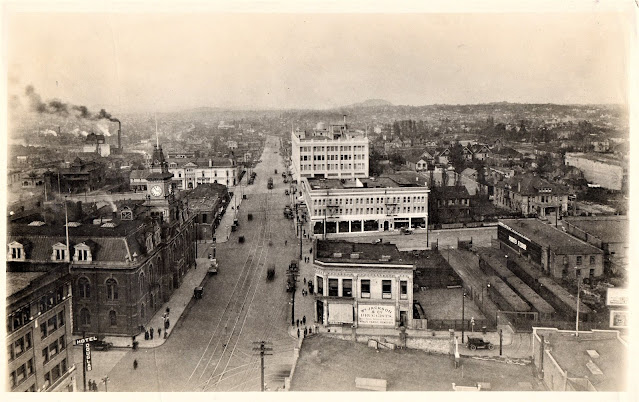

The idea that the inside and the exterior of a house could be unified with the building's immediate surroundings was a staple of arts-and-crafts thinking on both sides of the Atlantic. Design parameters were needed in order to achieve this synthesis, and in North America the popular vehicle for these turned out to be the bungalow, especially as conceived for life in sunny southern California. This feat took place systematically in Los Angeles, where a genial climate and sustained in-migration saw modern subdivision-style development appear on a massive scale (between 1900 and 1910, LA nearly tripled in size; between 1910 and 1920, it nearly doubled). Many of the new subdivision homes bought by newcomers were bungalows, a building type already in vogue as recreational housing, many designed by architects despite being marketed as housing for the middle class. Essentially, a bungalow is a one-storey building with the principal rooms gathered under a massive gabled roof, but artful designers sometimes clustered these internal spaces under a collection of roof forms. Sometimes the attic was also used for additional space, by means of a shallow dormer; often the predominant roofline, pushed well out over its walls for sheltering effect, also sported subsidiary gables projecting over important spaces like verandahs and bay windows.

|

| California-style bungalow, beckoning front verandah, set relatively close to the ground |

The modern west coast version of the bungalow grew from an earlier British adaptation of a rural Bengali house for colonial administrators and officers. Bungalows of all eras share certain defining features, like being cottagey, sitting close to the ground and, especially when architect-designed, rambling out into the landscape with cross-gables or projections - all features conferring a marked horizontal effect in contrast to multi-storied houses. Bungalows also came equipped with all the amenities of their day, in order to better meet first European, and later American, expectations of domestic comfort. The typical California-style bungalow sported a shallow-pitched gable roof (there were no snow loads to deal with) and was set on a concrete pad placed directly on grade (or in the case of the Savage bungalow, over a low crawlspace) making the house feel as if glued to the ground. Another singular feature is that no matter how small the overall footprint (and they could be diminutive), the bungalow always came with a substantial verandah employed so as to give it a distinctive look (there are hints of Japanese-temple woodwork in the California idiom). Over time the look adopted for bungalows would become synonymous in the public mind with the very idea of 'home' itself. The welcoming front verandah, combined with smart-looking exterior features like wooden siding and substantial sash windows, helped evoke cozy feelings among prospective buyers. What these engaging small buildings did with remarkable flair was to actively beckon to their clientele - people saw them and immediately wanted to inhabit one!

|

| California-style bungalow, timbered verandah across the entire frontage |

The bungalow as a housing type was exported from India to a number of Britain's other colonies in the nineteenth century, including Australia and what would later become Canada's westernmost province, British Columbia. From British Columbia, the house type likely migrated, by unknown routes, down the west coast before being re-imagined in Los Angeles. Here, it turned out, bungalows were being adapted for all modern North American cities. From the start, they were designed to embody a vision of 'the good life', which the design of the house was to provide for its residents. This vision anchored itself in feelings of coziness, smartness and up-to-dateness, in a house furnished with artistic wood finishes, built-ins like window seats, and all the latest domestic contrivances. One idea central to the vision was that the occupants aspired to enjoy an enhanced relationship with their immediate natural surroundings, which began with the way the house was intimately connected with them. Architects achieved this by featuring natural materials in construction, often with some rustic touches to intensify an arts-and-crafts effect. This was especially true of the use of local stone, often employed for foundations and for the massive piers supporting a typically impressive front verandah. Rustic effects were further magnified if the stone was actually gathered onsite or brought in from nearby. A lot of milled old growth wood was used as well, both outside and in, reinforcing the bungalow claim to naturalness. The shot below reveals the use of rounded river rock for foundation, chimney and piers, along with exposed timbers and planks on the exterior. Notice how this architect-designed bungalow appears to ramble outwards from its core.

|

| 1912 California bungalow with swooping porch roof on massive arroyo-stone piers |

Bungalows were marketed as a kind of stylized cottage in a gardened setting, an allusion their designers strove to maintain even as they crammed more and more of them onto uniformly platted streets. These homes came equipped with the latest in modern conveniences, which quickly included electricity and lighting, hot and cold running water, modern bathrooms and kitchens, and central heating (at least in parts of North America that needed it, which was nearly everywhere outside of southern California). Mechanical refrigeration wouldn't become widespread until the 1930s, but bungalow designers inventively incorporated a nifty feature known as a cooling cupboard into kitchens and pantries to help in preserving food. This device took advantage of something known as the 'stack effect', based on hot air's tendency to rise and, if provided with an escape in the form of a vent, its effect of pulling cooler air in behind it through a lower vent. These cooling cupboards were widespread in the era before refrigeration (especially on the coast), and necessary until such time as the icebox (and weekly ice delivery service) reached customers.

Suburban buildings from the outset, bungalows were regularly built on the outskirts of settlements and readily became ideal subdivision housing. The ubiquitous front verandah, championed as a virtue by the progressive movement in America, was fancifully elaborated in order to dramatically announce house to street. This really clicked as an architectural device, so monumental styling of verandahs quickly came to define the building's look in ways that allowed designers to individualize it for the market. Personality was expressed via the porch. Always roofed, often projecting from or settled into the principal gable, sometimes running across the entire front face of the building, always advancing and declaring itself in no uncertain terms, the verandah's commanding presence quickly came to stand for the bungalow itself. No matter how small the house, the front verandah was intended to make a statement and leave a lasting impression. And they really did! The verandah-as-signature-feature could be Japanesque, with piled timbers supported on chunky vertical posts resting on tapered piers of stone or brick. But it could also be framed up and set on tapered piers too. This combination of solid framing, heavy posts, and tapered stone piers, capped by an emphatically sheltering roof form, successfully caught the eye of most everyone who saw them. The example below, from north of Indianapolis, combines exposed rafter tails with timbered knee braces set on tapered brick piers.

|

| Verandahs, fancifully conceived, were key to bungalow character, here an effective mix of features |

As rendered architecturally, the North American version of the bungalow reinforced the links between building and surroundings, by design. Sometimes existing landscape features were built around, exaggerating the built-in look; more often, materials extracted from the site or from nearby were allowed to inform the look. Both techniques gave the impression the building derived from the site itself. Architects typically planned these bungalows within the limits of a smallish space envelope, offsetting lack of size by adding artistic interior features like wainscotting and exposed beams and exploiting technical devices in order to intensify or moderate climatic effects. The capture of light in the layout of rooms, of breezes out on the spacious verandah and inside via numerous opening windows, the access to glimpses of nature and garden from inside the rooms - all these elements were consciously explored in order to more intimately connect inside to outside. By design, bungalows intended to relate their occupants visually and experientially to both their surroundings and the possibilities of local climate. There were, it was felt back then, numerous benefits to bringing nature closer to the family in controllable ways.

|

| St. Francis Court, Pasadena, 1909: stone piers, exposed joinery, wood shingles. |

Southern California's moderate climate had a lot to do with launching the overall design direction for bungalows, but architectural responses derived in this benign climate somehow migrated wherever bungalows came to be built (which, over time, was pretty much everywhere!). The lightness of California construction required insulating and heating as the building moved northwards and winters became more severe; the desirability of central heating and weather-proofing led to them being built over full basements, which in turn pushed them further out of the ground in the Pacific Northwest (as well as making them more expensive to build). However, the spirit of visual openness to surroundings, along with controlled connection to nature and seasons, was absorbed into the building's DNA, and these features show up even in more-rigid suburban layouts on subdivision streets. In what follows, I try to illustrate how Victoria architect Hubert Savage went about bringing the outside into his house on the outskirts of Victoria back in 1913, and how he managed to keep this sense of connection to nature and surroundings alive throughout his home without sacrificing creature comforts or a sense of security against the elements. Also, I reveal how he took advantage of certain natural processes, like the stack effect, to more readily ventilate the house from heat buildup in the dog days of summer. As both client and architect, Savage enjoyed unparalleled freedom to experiment with designs blending artfulness, natural materials, relationships to surroundings and controlled exposure to the elements. With his arts-and-crafts tendencies and formal RIBA training, he seized the opportunity before him to lay out his own house and to place it picturesquely in a pristine landscape.

|

| Heavy timber posts chamfered for a more refined look on an elegant Victoria bungalow |

Early California bungalows were often built as recreational retreats, setting a fashion for siting them in pretty country locales where unspoiled nature provided both setting and views. In San Francisco and its environs, where natural landscapes ran together with residential enclaves, such dwellings were seen to afford escape into calmer, more artistic worlds, situated in healthier, more natural environments. By design, these bungalows encouraged families to experience the air, light, season and natural surroundings more fully, yet always in carefully controlled ways. One familiar example is the fashion for impressive wood-burning fireplaces, often made of fieldstone or sometimes of brick, done up decoratively with wooden surrounds and a massive wooden mantle piece. All this elaboration was not intended for heat advantage (in fact, the fireplace was often inefficient as a source of heat), but rather to prompt a relationship with fire as an elemental force - one that could be safely and pleasurably consumed in comfortable settings, drawing people together around a hearth that served as a natural family focal point. Even modest bungalows came with at least one grand fireplace, typically designed as the centrepiece of the living room, often accompanied by built-in bookshelves, with a tiled apron set into the floor in front of it. The crackle of a wood fire in the grate was thought to imbue family life with meaning, hearkening to earlier times in human history where our collective character was formed by telling tales around a blazing fire. This interest in building-in controlled forms of exposure to elemental forces and the seasons differs markedly from contemporary housing design, which prioritizes withdrawal and cocooning in interior worlds that are more fully insulated from, and less linked to, nature and climate. Arts-and-crafts designers were seeking precisely the opposite effect.

|

| Set in a landscape of oaks and other native species, a bungalow ensconced in nature |

Early bungalows were often placed in a landscape setting of picturesque scenery, which on the Savages' half acre involved an upland cluster of gnarly Garry oaks. Dramatically elevated by placement on a rocky outcrop, the house rises directly from the ground it sits on. A prominent gabled verandah flanked by projecting gabled bays lends upward movement to the building's ground-hugging facade. The landscape setting around it envelops the house, which in turn feels fitted-into its surroundings on the arts-and-crafts model. A low stone foundation, rising dramatically up into tall tapered piers that support a substantial verandah on trios of thick timber posts, imparts a certain grandeur to what is in fact a relatively modest footprint (perhaps 1350 square feet all in). The trio of upthrusting gables echo the shapes of trees in the tall fir forest fringing the oak meadows at back. The result is a lessening of the stark contrast between house and surroundings that appears rather unusual to eyes habituated to much blunter spatial appropriation.

|

| A curving stone path rises towards the verandah |

Up on its rise, this bungalow is approached from below along a gently sloped stone path with a sequence of steps and landings that reach the front door in a circuitous manner. Likely suggested as a route by the glaciated rock folds it traverses, the path leads visitors along the entire facade before reaching the front door. This indirectness further cements the impression of a house snugged into its surroundings, combining formality in appearance with a certain rusticity of placement in the landscape. The horizontal plane of the building's length is dramatized by the trio of cross gables, advancing from the main roof-line towards visitors and offering eye-catching details to anyone walking by. This is a house designed not just to be glimpsed on the way to the door, but to be enjoyed as an experience for the entire journey.

|

| A sheltered verandah with tapered stone columns |

Rustic use of local stone for the foundation and piers has the effect of making the building feel more a piece of its landscape. While obviously man-made, the bungalow declares its oneness with nature by displaying natural materials and allowing their worked character to ultimately frame its composition. This technique further blurs distinctions between outside and inside, an objective of both the English and American strands of the arts-and-crafts movement. Often the use of stone for foundations was continued inside into an elaborate stone fireplace, sometimes paired with a stone chimney (especially if the chimney is placed on an outside wall), strengthening the partnership between man and native materials. Bungalows were also often built with tapered or even squared piers made of brick, sometimes clinkered (over-fired), which could be fashioned as supports for an imposing front gable. Savage opted for a more rustic look with his stone foundation and piers.

|

| Rustic stone piers help fuse building and landform into a unity |

An expressive, beckoning verandah defines the California style of bungalow, serving to create a dynamic first impression and lending a truly inviting sense of entry to even quite modest structures. While verandahs may be less extensive on the American style of bungalow than on their colonial predecessors (where they would sometimes wrap around the entire building), they are nevertheless strikingly elaborated so as to play a defining role that strengthens street-presence. The verandah was integral to both the look and the function of the house, calibrated to present an overall feeling of welcome coziness along with safe refuge. While the fashion for porches was common in America before bungalows, these buildings presented an entirely novel version of the verandah that gave the building some serious pizzazz.

|

| Tapered piers, low railings, solid construction of a verandah with knee braces |

Back in the day absolutely everyone wanted one of these, and looking at these structures nowadays, it's not hard to see why that was. Often elaborately furnished with over-scaled, stacked timbering, a sheltered verandah on solid piers came to define the bungalow look. The verandah Savage designed not only offers shelter from the elements, it also creates a transitional space that's handy and needed in Victoria's long wet winter. At the same time, this space functions as an outdoor room that is shaded and breezy in spring, summer and fall. Verandahs like these also convey an intimate welcome to nature's realm, bringing it closer to the house by extending a sitting space out into it.

|

| Stone steps leading to an elegant outdoor room |

|

| Well-removed from the road below, an inviting perch on an early spring day |

|

| The temptation to enjoy a seat (and a coffee) in the surroundings is built in |

Verandahs provided both indoor and outdoor space, sheltered yet connected to the world at large, functional yet invitingly social and intimate, transitional yet inviting one to linger. You can be both in the setting enjoying the daylight and whatever gentle breeze there might be, and slightly removed from the outdoors and protected if need be. Prospect-and-refuge theory tells us that environments of this kind appeal deeply to humans at unconscious levels, especially when positioned well away from the roadway below. Here, high up on the rocky outcrop, the verandah feels like an aerie that's comfortably removed from the passing world. Low railings with a timbered look (above) define the enclosed space while also serving as informal seating for guests, offering an inviting perch from which nature may be unobtrusively observed.

|

| East light offsets the original dark wood panelling |

The simplest and most direct way to bring the outside into a house is to ensure that light penetrates deep into its recesses. One way to do this is by placing it on a rise and running its length from north to south, so its long walls face east and west, which is how Savage placed his bungalow. Another is to give it ample windows to let the light in. Pictured above, a large, low window on an east-facing wall admits morning light to the core of the house, offsetting the darkened wood interior (an original feature). The use of exposed wood inside the house makes the building feel like an expression of native materials, while the illumination of interior space with natural light brings these materials to life. Here the designer has been able to capture light through windows despite the verandah roof shading the front doorway; this is because the building's elevated placement in turn affects sun angles, which lets daylight reach deeper into the rooms as the sun works its way around the house. This bungalow is also just two rooms and a hallway deep, so there is penetration of the interior by light throughout the year. Blinds are desirable especially in summer because at various times of day direct light can actually be too intense!

|

| A window used to frame views of nature and building |

Buildings that are planned to optimize interior light effects while simultaneously capturing exterior views have a certain magic to them. There's a lightness to the rooms despite the weight of the extensive darkened wood paneling (see below). Glimpses of exterior elements of the house from inside the building also increase the impression of spaciousness in layout, a vital ingredient in more-compact dwellings. Visual links to the exterior extend a sense of intimacy with immediate surroundings, causing an engaging impression that was skillfully worked up by its designer. A variety of large opening windows, courtesy of easy-to-operate sash design, makes it possible to bring the day's elements right into the house, both as light and in the form of ventilation. In the living room pictured below, compact venetian-style blinds (a contemporary adaptation) afford much-needed solar control whenever sun angles send invasive quantities of energy into the room. In this setting, the immediacy of trees, especially some substantial firs down slope, provide an agreeable partial screen for direct sunlight.

|

| Ample windows allow light in while affording views, shown here in the living room |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Windows in a projecting bay extend into the landscape while capturing views |

|

| Light from south facing windows blasts the living room, warming it visually |

Bungalows use built-in furnishings to make efficient use of limited interior spaces, as these encroach less into space than free-standing furniture. Some people think this makes a virtue of necessity in what is, by modern standards, a spatially limited environment, but the fact is, it actually works. Built-ins are one of the many schemes bungalow designers deployed to optimize the functionality of compact spaces while amplifying their perceived spaciousness. The literature of the era is replete with humour about the mildly obsessive use of every square inch of interior space for some sort of built-in or other, from inglenooks to sideboards and even ironing boards. The analogy with how space is turned to account in yacht design is perhaps not inapt. But built-ins can also work to help make rooms feel cozier while adding the visual interest of high quality finishing materials to designs. One highly pleasing form of built-in is the window seat - literally a seat fitted into a small bay or nook that projects out into the world, if only just slightly. This not only effects jogs in exterior walls, which makes the building feel more fitted into its physical surroundings, it also adds charm and convenience to interiors. Window seats serve as intimate, much-loved spaces for sitting, reading and sipping coffee, or conversing with another person, all of which happens in what feels like a gardened or landscaped setting. In this sense, window seats function as an outdoor room in miniature.

|

| Window seat with casements draws nature nearer |

|

| Indirect morning light expands the apparent size of a modest dining room |

As Sarah Susanka, author of The Not So Big House and other works on home design, points out, a seat built into a window can also serve as a device to capture additional light for the room. Above, a leaded-glass transom window and wood-panelled sidewalls admit and reflect more light than a standard window casing, functioning as a kind of light fixture that's framed right into the wall. The source of light is external and obeys its own commands rather than those of a switch, but the glazing and the layered surfaces admit this found-light deep into the room. The effect is to make it feel both more inviting and larger than if it were less well illuminated.

|

| Once open to the elements, now with a built-in window seat |

Rooms with excellent sun access, generous window space and built-in seating not only invite us to nestle right into the view, they also bring the view dramatically closer to us, sometimes right up to the windows. This makes it easier to remain in touch with the day and with seasonal effects while staying inside the house. Light and season guarantee a continually changing scene, from day to day and month to month. The room pictured above, designed as a summer tea room that was once open to the elements, was eventually enclosed, re-muddled abusively, and stayed that way until steps were taken to set it right. The leaded-glass casements and built-in window seat now combine with the original barrel-vaulted ceiling to create an inviting space that feels as though it's a piece of the garden itself.

| ||||||||||||||

| Windows framing views that change with the season, here in autumn | |

|

| Same window, this time revealing a lush early spring garden scene |

In the Hubert Savage bungalow, all of the windows have been treated as opportunities to capture views, admit light and air, and relieve the heaviness of blank walls. By connecting inside to outside visually on three sides, the house itself becomes a vehicle for capturing views. It succeeds in tapping into what the Japanese call 'borrowed scenery', in essence framing the natural surroundings to be seen as views from within. Many of the windows also open, both top and bottom, optimizing opportunities for ventilation of individual rooms (again allowing hot air out at the top, pulling cooler air in down below). Ambient light is caused to penetrate the building's interior by dint of its long east-west walls.

|

| Late afternoon summer light reaches deep into the kitchen, imparting a warm glow |

Above, generous sash windows set low in the wall plane invite sunlight deep into the interior, visually warming the rooms and connecting occupants directly to the day while drawing the eye out into surrounding greenery. Even in the weaker light of winter there's considerable solar gain and the interiors are visually warmed into a cozy, inviting space (heat is however still very much required!). These large, vertical windows are set a mere thirty inches from the floor, strengthening visual access to the sheltered garden beyond. Pictured below is our tiny central corridor, an intermediate space that gives access to no fewer than seven doorways! The door at the end of the hallway accesses our attic space, which in turn has a small north-facing window that opens. If on a sultry summer evening we open windows downstairs, then open the attic door and the attic window, hot air rushes out of the main floor space up into the attic and then flows out of the attic window. This is, once again, a conscious use of the stack effect to cool space, exploiting hot air's tendency to rise and pull cooler air in behind it. This effect is so strong that if you stand in the doorway to the attic when it's happening, you can feel the airflow moving swiftly through the opening. This form of ventilating to overcome excessive heat was expressly designed into these buildings.

|

| Light reaches deep into the central hallway |

The connection between inside and outside is further reinforced by setting the floor plate of the house very close to the earth. The original Anglo-Indian bungalow mimicked its indigenous forebears in sitting on a low plinth or platform placed near or directly upon the ground. The trend-setting California bungalow was similarly set near to, or in some cases right on, the land, a practice that gives a distinctive look while further fusing these buildings with their immediate surroundings. This was less likely to be done in Victoria, however, where it was the practice from early on to put a full basement under a house. Whether Hubert Savage's placement of his own bungalow close to ground level at the back reflected his English arts and crafts training or, perhaps more likely, the then-California fashion for placing a bungalow directly on grade, is hard to say. However, one does detect numerous features with California/Craftsman influences in the overall design of the house, and certainly enough to know that he was paying attention to the flow of design-ideas coming from California.

|

| Bumping wall planes outwards spreads the building out into the landscape |

|

| The exterior seen from inside reinforces their connection |

Bungalows have been described as 'rambling' because they can project out into the landscape by means of bumpouts and roof lifts. Projecting bays and other roofed devices used to vary the surface of wall planes serve to counter the sense of boxiness that can accompany a house. Architectural projections link the building more directly to its landscape, allowing it to feel fitted around the land's contours; this may in turn create opportunities to step the building up or down the land. Another device used successfully by arts-and-crafts architects involves intentionally catching glimpses of the exterior of the building from within the house. Because the Savage bungalow's footprint was made irregular by design and its roof line is pushed well out over its walls, opportunities for such exterior glimpses abound. Above, kitchen windows afford views of a glazed door to the back porch, which advances out into the garden while offering a snug rear entry to the home. Below, a walk-in closet added years after the main building was erected is gained by projecting the rear wall outwards as a half-cabin and stepping it up a rising landform.

|

| A building set directly on the land seems to grow right out of the ground |

Hubert Savage chose to set a corner of the rear wall of his bungalow directly on the landform it crowns, further gluing it to the site (photo above). This cements the impression that building and landscape are one, making the house feel like it belongs just where it was built. At the back of the house, this placement gives access to a private garden realm entered almost imperceptibly from the main floor level (a drop of about fifteen inches). This in turn, visually, allows central living spaces to feel continuous with the gardened setting, emphasizing directly the sense of connection. Placement near ground level serves to pull the building downwards, so its entire mass feels accessible and more intimate at the back. In this way feelings of harmony between nature and dwelling are set in motion (picture below). Today this rock would likely be blasted out, the building pad leveled and extended for ease of construction, and the pre-existing relationships formed by retreating glaciers and advancing vegetation obliterated to allow construction of an over-scale home.

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| The building actually steps up the landform, knitting architecture and outcrops together | |

|

| The barge board was brought so close to ground its tail had to be clipped for safe movement |

Setting the building into the landscape as opposed to remaking the site for convenience demonstrates respect, bordering on reverence, for the natural surroundings. It also anchors the feeling that nature and garden run right up to the house, reinforcing the sense of synthesis and complicity between the two. In this conception, nature isn't simply a distant glimpse of what lies outside. Of course this gives the illusion that one is somehow in the garden while still inside the house, a feeling that is encompassing by design.Whether inside gazing outwards, standing in an intermediate space like a verandah, or standing outside in the garden, perhaps looking back towards the building, nature is always present and defining.

|

| The garden contrived as an enclave extends it as a series of outdoor rooms |

While the house is designed as an architectural object in a garden and the garden developed as a context for the house, both are designed to exist in harmony with the broader landscape setting. The Garry Oaks, native shrubs and flowers, and glaciated rocky outcrops retain elements of an original landscape setting for both house and garden (magically, many remnants of native landscape survived subdivision of an originally much larger lot). One way of furthering the explicit connection between building and surroundings is to contrive the garden as an informal series of outdoor rooms, linked together by paths. If these garden rooms are implied rather than bluntly stated, it's possible to achieve a subtle extension of architecture into surroundings that provides orientation for human use without reducing nature to a sequence of activity spaces. This form of composition, known traditionally as picturesque landscaping, is also a lens through which the building's siting can be seen more accurately.

|

| A patio 'room' of oblong pavers marks the transition from building to garden |

|

| Outdoor rooms arrange garden space and invite enjoyment of day and season |

Outdoor rooms, or compartments, have long been used successfully by artist-gardeners to blend house and garden into a unified whole. Bungalows lend themselves to this sort of treatment, both by dint of their history of being built in gardened compounds, and their architectural use of bump-outs and ancillary roof forms to extend irregularly into natural spaces. Also, as historian Alan Gowans remarks (The Comfortable House), early suburban homes of all types, and foremost among them bungalows, were novel in being designed to be seen from all four sides, often coming equipped with side and back doors, additional or wrap-around porches, and circulating pathways. This stands in sharp contrast to more vertical, street-oriented Victorian housing, as well as to modern planned suburbia, which often presents double garage doors and an undistinguished front door to the street while neglecting side facades in favour of interior spatial gain. All of which leads to a diminished sense of visual connection to the exterior of the house, affecting its potential to galvanize intimacy for its occupants.

|

| Loose arrangement of sitting spaces integrates well with the remnant oak meadow |

Seasonal changes and weather patterns affect the overall mood of the place, but this bungalow is designed to enable occupants to enjoy nature to whatever extent climate and day allow. Winter sleet or spring rains can be equally enjoyable as experience if the nature of the shelter allows us to observe them while keeping ourselves warm and dry. The management of precipitation, as rain or snow, is an important aspect of all house design, and the bungalow with its sheltering roof form affords a sense of security that permits enjoyment of even inclement weathers. The large and frequent window openings also enable the weather to be more agreeably watched, as an event happening around one, yet kept at a safe remove. This can however lose its charm quickly if weather is unchanging and insistent, as it can be in our typically dreary month of November here on southern Vancouver Island!

|

| Even April sleet serves as an interesting spectacle glimpsed from a sheltered verandah |

|

| Pale light in winter, on natural and built objects, creates a scene of the moment |

A complex and intimate relationship between a building opened to its surroundings and a natural or gardened setting is now decidedly old-fashioned, something the modern eye has been conditioned not to seek or even to notice should it appear. Subdivision development typically maximizes interior space, leaving only shallow setback strips between houses and paving over much of what might have been front garden to accommodate the automobile. Proximity of neighbouring buildings means sidewalls often have few windows and there is rarely a reason to look at or go to the spaces in between buildings, other than to mow whatever lawn exists there. Also, more generous landscape settings around older homes rarely survive generational changes in ownership, as there is simply too much money to be made by raiding the development larder, whether through subdivision or by tearing down the historic structure and then building out the entire bulky cube defined by contemporary setbacks.

Remnants of early suburbia displaying a balance between built objects and their surroundings reflect an openness and curiosity that people were, for a time, encouraged to explore in the very way their homes were designed. While this is arguably romanticization of nature (which, as we know, is hardly benign), it has the virtue of opening realms of pleasurable experience that can transform a mere house into a home-in-a-garden. Buildings with these attributes remain suggestive of ways of dwelling that engage us directly in observing and tending our surroundings while exposing us in controlled, hence pleasurable, ways to the variety of nature's moods. But, anyone tempted towards this sort of situation had better be interested in gardening, or at least prepared to manage landscape actively, because nature really does want to run right up to the door, and living closer to it is definitely a hands-on experience.

|

| You had better enjoy gardening if you choose a country locale |

This is the third in a series of posts in the centennial year of the Hubert Savage bungalow, intended to celebrate and share the house's history and character with the community. In March we were invited to receive an award of merit from the Victoria Hallmark Heritage Society, in recognition of our efforts to restore and preserve this antique house. I have gratefully accepted this proposal, while remaining all-too-aware that complete restoration of a 100-year-old wooden house is a moving target and a project that might well outrun my own efforts at stewardship. The awards ceremony is the evening of May 7th at St. Ann's Academy in Victoria, B.C.

Next post: a printed frieze by English artist Lawson Wood adds an artistic touch as a built-in feature in the Savage bungalow's living room.

This post was amended, edited and updated in early 2021. The author can be reached at cubbs@telus.net .