When Hubert Savage elected to build a country bungalow five kilometres out of town back in 1913, his was likely the first house on then-Blackwood Road and one of only a handful in that part of Saanich. The question is, why ever did he opt to locate way out in the back of beyond rather than on a more settled street closer to downtown? And, however did he get back and forth in those days, given the locale's relative remoteness and the need to commute to his office downtown? This all transpired before the private automobile had become a realistic option. Speculation about the links between a novel form of personal mobility and the early dispersal of suburbia into rural lands forms the basis of this post.

In his classic history of suburbia, Bourgeois Utopias, Robert Fishman recounts how the idea originated with wealthy British merchants who opted to build homes out in unspoiled countryside, a move that enabled them to flee the horrors of the industrial city they had created without having to sacrifice urban comforts. The impetus to move home to a rural locale became the opportunity to breathe cleaner air, gain more space for gardens and other outdoor pursuits, and especially, to raise family at a secure distance from the clamorous city. Additionally, rural land was dirt cheap to acquire because, up to the point of becoming accessible to development, it was typically either farmland or bush.

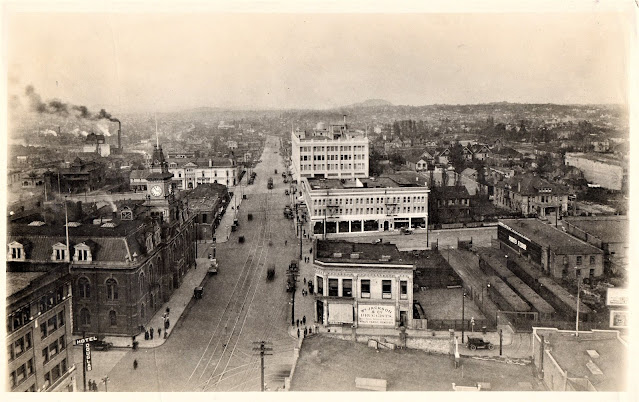

Fishman says this wish to flee the pitfalls of urban conditions lies behind the suburban aspiration, coupled with a hope of finding a safer haven nestled in nature's bosom. But for urbanites, choosing to relocate to the country means radical separation of the work and home milieus. This was initially only feasible for those wealthy enough to finance a dependable means of transport between their remote residence and their place of work. The choice to live this way only became more widespread with the advent of cheaper, more frequent and reliable forms of mobility. Initially, it was prompted by steam locomotion, which in the US in particular generated decidedly upper-end suburbs, often at a considerable remove from town. But from the early 1890s on, electric-powered streetcars appeared in many cities subject to rapid population growth. Electric street railways provided a new form of mobility that opened access to large areas of unbuilt land on the immediate periphery of town, and at much lower prices than town lots. In Victoria's striking coastal setting, such lands often came with picturesque scenery. So these new electric streetcar systems quickly led to suburban colonization of former farms and hillsides in immediate outlying areas. Victoria's first streetcar system, the third in the country, quickly gave rise to a number of small, inner ring suburbs on the outskirts of previously settled areas. Convenient access from these new suburban enclaves to the town centre, where jobs and shops were clustered, was the vital selling point of the daily real estate adverts flogging both land for investing and newly built houses. The connection between the electric streetcar network and the opening up of new zones for development was front-of-mind for those financially backing these schemes.

Fishman also shows that new suburban developments tended to cluster around stops along the new corridors, within easy walking distance of the means of mobility. Streetcars thus opened up the suburban option to the waves of people then flooding into urban regions looking for new economic opportunities and places to live. The form this more far-flung, rail-based suburbia took differs markedly from the more uniform shape it came to assume in the subsequent era of automobile transport. When cars eventually took over from the trains, a combination of cheapened house design, greater uniformity of look and lot size, and less-imaginative building placement (due to uniform setback requirements and subdivision-scale planning) would generate far-more anodyne outcomes. But up to 1920 at least, electric street railways and Interurban lines were the defining vehicles of regional mobility. They not only allowed for greater spatial separation of home and work, but also prompted entirely new relationships with regional attractions and activities beyond the range previously accessible on foot. The fact that land costs in outlying areas were very low also prompted subdivision patterns that tended to retain more of the look of countryside, resulting in houses set back from the road on lots with residual scenic features. Early suburban developers working in Los Angeles actually financed and constructed electric street railways in order to facilitate their speculative housing projects. The ready supply of newcomers meant rising demand for just such suburban spaces: a comfortable house, within easy commuting distance of work and, courtesy of abundant materials and cheap land, affordable for little more than the cost of renting in town. Anywhere within walking distance of a stop qualified for this new suburban homesteading, a feature that in turn served to 'democratize' residential housing choices.

Cheap but high-quality building materials, like knot-free old growth Douglas Fir and durable cedar shingles, flew out of custom milling operations in large quantities around Victoria, contributing to the superb value-proposition a new house then represented. The ready availability of these quality materials also predisposed contractors to erect housing 'on spec', meaning it was made for the market without particular buyers commissioning the work. Another, even more important, factor affecting the value proposition of a house was the sheer cheapness of land on the periphery of town. So the revolution in transport galvanized the settlement of outlying suburbs, enabling home ownership for a rising share of the population. In the long boom that began about 1890 and ran well into 1913, the emerging housing market fuelled new heights of speculation in land development - turning it into a party that everyone in town was invited to!

|

| Garden City real estate play occasioned by the Saanich Interurban Railway |

Out in the Garden City suburb, well before the new line was up and running, investors were busy marketing quarter-acre blocks of land for between $450 and $600, which in present-day dollars is a mere pittance. Four hundred and fifty dollars in 1913 equates to about $11,830 in today's dollars, while $600 is about $15,774. Let those figures sink in for a moment. Then consider that in December 2020, a chunk of raw land designated residential in Strawberry Vale had an asking price of $599,000. The difference between those two figures indicates how much inflated land-values structure contemporary prices, and illustrate what a bargain the 1913 land price represented. The same is true, albeit not nearly so dramatically, for the relative value of buildings back then. In 1913, you could buy a deluxe bungalow near the edge of town, on a full basement, for as little as $3500. Translated into today's dollars, that is roughly the equivalent of $91,000. So a 1400-square-foot smartly dressed house could be had for the equivalent of $91,000 in today's money (also including the land it was sitting on) or a cost of about $65 a square foot nowadays. Today a 2300 square foot 'standard' home, not including land, would cost $460,000 to $690,000 to build ($200-300 a square foot), and if it were done up with 'luxury' finishing (i.e., done to bungalow standards) it could run as high as $400 per square foot (or six times the 1913 cost of house and land rendered in today's dollars). Comparative costs of constructing homes also underscore just how good a deal the house-and-land package was back then. It's absolutely true that the land the building sits on is now ridiculously more costly than it was originally: 38 times more expensive today to buy the development potential of a featureless RS-4 lot on a busy street than it was to purchase a deluxe quarter-acre block in the Garden City suburb. No wonder Hubert and Alys were interested!

The advent of electric street railways triggered the growth of rings of suburban outskirts around urban cores in booming cities across North America. In Victoria, electric streetcar service resulted in the populating of outlying areas like Fernwood, Fairfield, Hillside, Oak Bay and finally Burnside/Gorge. Towards the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, continuing in-migration fuelled a rising demand for suburban housing, creating conditions in which an exciting extension of the street car network, known as an 'Interurban' line, seemed economically feasible. Interurbans were faster electric systems - essentially precursors of today's light rail transit (LRT) - differing from on-street trams in having exclusive rights of way to run in. Sleek and classy additions to existing urban infrastructures, Interurban lines connected regional centres in novel ways, often taking their host region by storm while rapidly accelerating the dispersal of people into previously unpopulated areas. This power to disperse for residential purposes while, at the other end, assembling for jobs and shopping worked in tandem with local real estate interests to enable the marketing of new housing possibilities. By 1913 there was so much impetus in real estate speculation that tiny Victoria, population around 45,000, had over 300 real estate agencies in operation!

Hubert Savage's chance to live out in the country while working in town arose precisely because this new Interurban railway made the daily commute feasible. As a practicing city architect, he needed reliable transport from what was then a considerable distance. A recent ex-Londoner, he was perhaps already accustomed to using mass transit to get around a region, a habit that would have helped him view living out along a rail corridor as practical. Articling as an architect in London, England, he'd also likely been absorbing the growing English fascination with recreational use of the countryside, closely associated with a novel building type known as a 'bungalow' - recently imported from colonial India. Arts-and-Crafts architect R.A. Briggs was popularizing (among people of means) the idea of locating small, artistic bungalows for recreational use out in pristine countryside; his Bungalows and Country Residences (1891) preached the benefits of a new style of 'free and easy living' they made possible in scenic locales with convenient access to the metropolis. Certainly in England this choice was largely restricted to those with gobs of money, and what Briggs proposed as recreational getaways were not exactly small houses. But in spacious, enterprising North America, with an entirely different value-proposition on offer, the idea of a country bungalow was a whole other thing.

Such factors may have predisposed Savage to feel comfortable choosing a remote building site in then-distant Strawberry Vale, itself part of a newly organized district municipality known as Saanich (1906). Saanich (an anglicization of WSANEC, the Coast Salish name for the area) then comprised sparsely inhabited rural lands that were once part of First Nations' traditional territory. At the time, and certainly to a town eye, Strawberry Vale and its neighbouring Marigold district weren't much more than a few rural farms ringed by rocky outcrops and stands of native vegetation. One of the area's attractions was surely the low price of land-access, another the opportunity to inhabit some truly picturesque landscape on an upland slope. Perhaps that's what led the Savages to purchase a half-acre lot, with distinctive landscape advantages.

A look around the area's built-out suburban streets today shows a collection of mostly modest, mainly single-storey houses dating from a variety of eras, a few still located scenically on larger parcels of land. Built loosely on a grid pattern but with some culs-de-sac courtesy of the steep Wilkinson escarpment, the Garden City suburb still retains a degree of natural landscape and native vegetation on its many upland sites. A glance around the locale today suggests its pattern wasn’t contrived by a single planner or builder, but rather grew gradually from infill of a more eclectic kind, accelerating in the 1960s housing boom. Its primary assets today are an unpretentious mix of housing and its residual greenery. Since the early nineties, when Saanich Council opted to stand firm on the idea of urban containment, this area has been undergoing infill development at a fairly rapid rate (and often not very compatibly, as below).

One does observe too that the more recently built the home, the less modest and more mammoth the outcome tends to be. Garage doors appear and come to define facades, frontages come much closer to roads, setbacks are ever-more uniform. The biggest of these new houses fully occupy the smaller lots that are carved out of vestiges of earlier suburbia, where buildings tended to be sited well back from the road, in more generous landscape settings, and in greater sympathy with the lie of the land. This idea of a house placed carefully in a distinctive landscape contrasts sharply with the more packed-in and built-up feeling of both the urban core and later auto-oriented suburbia. Early layouts of rural suburbs were based more on integrating town and country in a way that achieved a balance, an explicit objective of the English Arts-and-Crafts movement.

If Marigold's layout now resembles many another auto-centric suburbia, it was anything but that back in 1913. Mostly it was bush and stumps, and the prospect of it being anything other only arose because an electric Interurban line punched its way through the precinct. When plans for this major capital project were first revealed, speculators quickly bought land in anticipation of the rapid development they expected it to galvanize. It was named Garden City, a rather lame attempt to coat-tail Ebenezer Howard’s then-popular idea for self-sufficient garden cities (like Letchworth, pictured above). But beyond naming streets after common garden flowers like zinnias and hyacinths and lilacs, there's no evidence of Howard-like thinking behind this real estate play - just the desire to harvest a fresh bonanza of real estate froth on the fringes of town. Growth had typically followed rail lines, so the would-be subdividers of Garden City were confident it was coming their way. It certainly had gone that way all across the Lower Mainland too! And the ad below, the bottom section of the one discussed above, shows just how widely the net was cast in the run-up to the beginning of rail service. Prospective buyers were invited to "get in on the ground floor," "as the prices now offered will undoubtedly double as soon as the car line is in operation". That was real estate speculation in motion, but solidly grounded in what had been happening around the region for some time. Indeed, it was the pattern emerging in Victoria wherever streetcars gave people ready access to residential property. Victoria historian Harry Gregson notes that Fairfield "became one of the most popular residential areas and 60 X 120 foot lots were selling for $5,000 in 1912 compared with $400 six years earlier." One had only to find the wherewithal to buy in, and voila, riches would surely follow.

The privately owned BC Electric Railway Company (BCERC) decided to build this chic commuter service expressly to open up what they hoped would quickly become thriving residential enclaves along the western side of the Saanich peninsula. With a legislated monopoly to supply power and street-transport services in both Vancouver and Victoria, the BCERC was already enjoying robust success operating longer Interurban rail lines throughout the Lower Mainland. As the operators of Victoria's highly successful streetcar system, the BCERC brass were convinced that Victoria's hinterlands were similarly poised for residential takeoff, and they were keen to be both catalysts and beneficiaries of this growth. Adaptation of electricity to power lights and other devices in residences was also just then taking off, so the BCERC, sole generator and distributor of electrical power in the region, saw real potential in the emerging market for suburban homes.

|

| Interurban Line, BC Electric Railway Company, in Chilliwack, 1910 |

Operating at higher speeds than streetcars sharing rights-of-way with other traffic, electric Interurbans vastly extended the possibility of new settlements setting up in outlying areas. In Los Angeles, railway spurs radiating outwards from a central spine allowed huge masses of people to work downtown

while retreating at night to citrus-grove subdivisions dotting the vast metropolitan plain. The same phenomenon spread to other city-regions, also subject to rapid in-migration as farm labour moved into cities, so there was really no reason to think anything different would happen in then-also-booming Victoria. And the new areas to be opened up were often as pretty as postcards, with views to fields, inlets, straits, lakes and mountains, so they were doubly marketable as housing. Yet in the end, despite a few scattered residential starts like the Savage bungalow, the hoped-for real-estate bonanza from the new Interurban line would simply fail to materialize. Late in 1913, and quite unexpectedly, the economy began tanking badly, virtually everywhere in North America. Then in 1914, world war broke out, and so by 1915, many young Victorians had enlisted in the army in order to fight for their country, dealing a further blow to local demand. For the Savage bungalow, the stalled economy meant that rather than his bungalow serving as the forerunner of a whole new housing trend (as its designer may once have imagined) it became instead a rather distant outlier - marooned in a street-car suburbia that never actually came to pass. For Savage himself, the gravity of the financial crisis would mean that for a time he had to work outside his credentialed profession of architect. As Garden City failed to materialize around the rail-line as planned, the rural land it was to be platted from remained mostly cow pasture, rocky outcrops and oak-and-fir-clad hillsides for a good many decades to come. The form the neighbourhood took when it eventually did fill-in derived more from the primacy of automobile travel, and the sixties in-migration to Victoria, embodying on the whole a far less romantic, vastly more prosaic, vision of suburbia than than the suddenly outdated idea of 'town in country'.

None of this would necessarily have detracted from Hubert Savage’s plans to create a rural refuge for his own family in a pretty place, which came to fruition in tandem with the Saanich Interurban line's construction (an effort that cost nearly $1-million back in 1913). Some 23 miles long in total, with thirty-one stops and sheltered wooden platforms, this well-engineered electrified line enjoyed its own right of way north from Tillicum Station junction, continuing all the way out to Deep Bay on the Saanich Peninsula. From Tillicum Station inbound, the line shared Burnside Road with the streetcars en route to a convenient downtown terminus across from City Hall.

|

| Dignitaries awaiting the Saanich Interurban Line's inaugural ride |

The first of the new rural stops along the Saanich line was called Marigold, after Marigold Avenue, which was less than a kilometre from Savage’s new digs on Blackwood Road (today Grange Road). Its second stop was Blackwood station, marginally closer to the Savage bungalow but apparently costing a nickel more for passage. I can easily picture a smartly dressed Hubert Savage walking a wee bit further each day in order to effect that significant saving, and feeling pleased with himself for getting exercise into the bargain.

|

| Commercial cluster, Marigold station, Saanich Interurban line, ca 1923 |

Construction of the Savage bungalow was

likely in full swing when rail service commenced on June 18, 1913.

There was plenty of regional boosterism around the Interurban line's big opening, the train

festooned with ribbons and laden with a cargo of some 100 dignitaries for its

inaugural ride. It even featured a ceremony with Premier McBride symbolically driving a last

spike out at Deep Bay (picture, two above), where the BCERC would soon build a chalet-restaurant as a destination in order to draw

more sightseers. The initial service was a two-car train with comfortable seats and

a smoking section, offering many return trips per day. If Savage caught

the 7:30 morning train at Blackwood station, or the 7:32 at Marigold station, he was downtown by

7:50 and could be at his drafting table by eight. The return trip would have been equally

convenient, punctuated perhaps with a stop for groceries or sundries at

one of the country stores located near Marigold junction (pictured above, looking a bit down-at-the-heels, in 1923).

It is undoubtedly true that Savage’s choice of such a remote building site was determined by this new and convenient method of commuting. Access to town water and electricity may also have played a role (the new number one water main from Sooke Lake was buried under nearby Burnside Road, opened in 1915). The house came equipped with an electrical system (knob-and-tube wiring) which initially fed overhead lights and several wall outlets per room, as well as front and back outside lights that illuminated the night. We can be certain that just this sort of suburban homesteading was what the Interurban's builders were counting on to generate future demand for electricity (both as passengers using the trains, and as domestic consumers). Embryonic markets for the power it was generating are the sole explanation for the BCERC making such a huge investment in rural passenger service. And, back in the day, it was just the sort of artistic, low-slung bungalow that Savage designed for himself that was proving a highly attractive lifestyle choice to the droves of newcomers filling North American cities.

If privately owned electric railways were contrived for the purpose of opening access to unbelievably cheap rural lands, real estate speculation was central to the equation. Interurbans were faster and more reliable than competitor railroads from the previous era of steam. They were in effect as distinctly contemporary an idea as the low, horizontal houses then finding favour with the newly minted suburbanites. Railway promoters and development interests in fact often operated as part of a single development scheme. Where the formula worked, settlements mushroomed around the stops on patterns of convenient walking access to the regularly scheduled trains. The Saanich Interurban's effect differed only in degree from patterns set in motion by the downtown streetcar system, which also sparked new neighbourhoods around its stops, albeit more tightly spaced and closer to the downtown core. One impact of covering greater distances more rapidly was to in fact physically disperse suburbia much further outwards.

However, to the great dismay of its investors, the Saanich Interurban line didn't spur the desired galloping growth, despite all the investment, fanfare and sustained effort to market its advantages. And then the economic boom that had been raising all boats for so long fizzled out just as competition from rubber-tired vehicles began filching the railroad's clientele. And picturesque little Victoria, distant from the major movements of goods and people animating larger centres, was not destined to be the people-magnet the port of Vancouver became as Canada's major west-coast trans-shipment point. So it would transpire that, little more than a decade after its opening, the Saanich line's prospects had dimmed to such an extent that it had to be shut down. Soon after that, its tracks and overhead wiring ripped out, it was made to suffer the ultimate indignity of conversion to municipal roadway - hence the level quality of the Interurban Road we still use to this day. The boom that went bust after 1913 wouldn’t return to Victoria until well after the Great Depression and a second global war, then still decades away. People who invested in parcels along the line hoping to get rich were left holding the bag well into the sixties before there was fresh hope of redemption.

In 1913 the immediate threat to the Saanich Interurban line was posed by cut-throat competition from vehicles making free use of public roads provided by civic tax revenues. If electric railways easily bested the older steam railways, they in turn were quickly trumped by the introduction of gas-powered automobiles. Soon after the Saanich Interurban line opened for business, dozens of ‘jitney’ cabs (or small buses) appeared out of the blue to compete for the rail clientele ('jitney' was slang for a nickel, the uniform price of a ride). By November 1913, over fifty such jitneys were operating in Victoria. By 1915, there were 150 of them, with an association (Victoria Jitney Association) to fend off municipal regulation.

With low operating costs and the ability to offer door-to-door service, jitneys posed a running threat to streetcar systems everywhere. Drivers cruised the stations in advance of the trains, scooping up riders with cheap fares and the chance to experience movement in one of these strange self-propelled contraptions. Widespread use of jitneys thus contributed to the early demise of many Interurban lines, whose relatively high capital and operating costs meant they couldn't compete on fares without virtually bankrupting themselves. Jitneys not only established prototype taxi and bus services, they also helped pave the way for the rapid spread of the private automobile, by far the deadliest competitor for any other form of mass transit.

While Interurban trains effectively linked regional centres, the new settlement patterns they sponsored were spread at broader

intervals along their longer lengths. This pattern of growth leapfrogged a huge amount of

undeveloped residential land that sat much closer to downtown, land that was potentially cheaper to service

and offered shorter commutes once there was an alternative to fixed-link streetcars. Steady extension of paved roads by local municipalities made it easier for people to adopt automobiles, which helped in turn open up many previously unbuilt areas lying between existing streetcar lines at greater than walking distance. These locales came with rural, hillside and seaside settings too, giving them a resort-like or country feeling that in Victoria still persists to some extent to this day.

If Hubert Savage was counting on a train-based extension of suburbia to expand his architectural practice, he was doomed to disappointment. My guess, however, is that he chose this locale for its intrinsic merits as much as for business reasons, realizing that his own family would get to enjoy a pretty spot far from the crush of newcomers for a great many years to come. The idea of retreating to the country was very much in the air at the time, and architects discovered it could be made practical using the novel housing type known as a bungalow as the basic building block. R.A. Brigg's writings advocated finding a pretty place in the countryside and simply popping a building onto it, thus enabling a family to enjoy a lifestyle 'of rusticity and ease'. Gustav Stickley's The Craftsman magazine advocated much the same thing too. And that's pretty much what Hubert and Alys Savage did way out in Strawberry Vale. The bungalow, reinvented prosaically in Los Angeles as subdivision housing, would prove the perfect medium for this outward movement all across land-rich North America, providing safe haven and creature comforts in gardened settings. It's no surprise that Hubert and Alys wanted this experience for themselves.

To return to the rapidly changing mobility equation: if the low fares offered by the jitneys bled the Interurban lines, the rapid rise of the private automobile delivered the coup de grace. Canadian streetcar historian Henry Ewart says that jitneys served to introduce people to the idea of car travel while demonstrating its profound utility. The car's advantages of flexibility (leave on your own schedule) and convenience (weather protected and secure), coupled with its continually falling price-tag once mass production got rolling, made it truly unstoppable - especially once municipalities were invested in the business of paving roads.

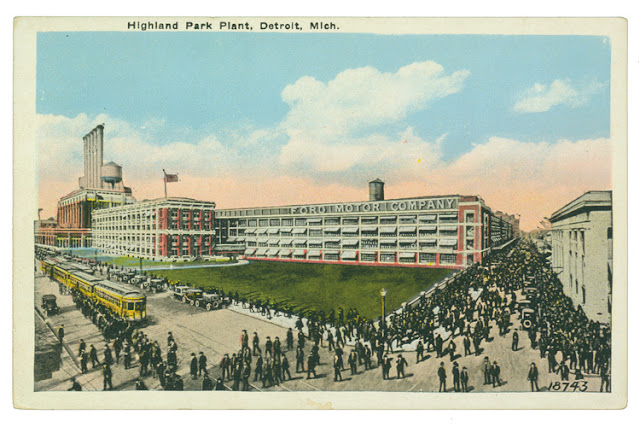

In an even deeper irony, unknown to either electric railway builders or suburban homesteaders back in 1913, Henry Ford was just then successfully introducing the moving production line to car manufacture (photo above). His pioneering leap into automated production cut the time needed to build a car chassis from some 12 hours to just 2.5! This innovation dramatically increased his factory's output while in turn lowering the price of its products, guaranteeing growing markets for the private automobile. It also allowed Ford ultimately to introduce the $5 working day (which led his competitors to accuse him of being a socialist!) a feat that meant his own workers could actually aspire to own the fruits of their own labour. Far from implying any socialist inclination, Ford's wage increase was aimed at improving retention of workers who had to endure the relentless monotony of the moving production line.

We don't know at what point Hubert Savage abandoned the train and began commuting to work by car, but the Interurban option had shut down by 1924, just 11 years after startup. Even the extreme measures taken by Vancouver and Victoria city councils late in the day to formally ban jitneys from cruising rail stops for customers wouldn’t prove sufficient to save the Saanich Interurban. It was perhaps prophetic that Saanich, home to the region's first and only electric Interurban railway, took no action to curb the use of jitney cabs at stops. Perhaps the council of the day was early to recognize that automobile travel represented the real wave of the future?

So the owners of the rail-inspired Garden City suburb had little choice but to adapt to growing automobility from early on. Yet, given its distance from downtown in a now-slow-growing city, this relative remoteness meant incremental rather than rapid build-out, and ultimately of a more modest nature than initially envisaged. Of course, Savage's bungalow was quite indifferent to how it was accessed, and it certainly didn't require a built-up neighbourhood crowding in on it. Its unique placement on a hilltop in the countryside only necessitated access to some form of viable mobility in order to overcome the separation of home and job and services. If suburbia does involve an element of escape from the crowding of town conditions, its precondition is inevitably some form of convenient mobility. Without it, suburbia can't really exist.

At the time it was built, the Savage bungalow would have appeared sleekly modern and entirely novel: radically horizontal in contrast to its Victorian forebears, forward-looking with its motion-minded kitchen and new electric appliances, isolated geographically yet connected with the broader world via telephone initially (services and friends) and then by radio (news and entertainments). While fully modern in its day, in true Arts-and-Crafts fashion it was consciously styled to appear firmly rooted in tradition, working closely with the landform beneath it, and built entirely from local wooden materials.

|

| Consciously styled to appear rooted in the past, offering fully modern living |

Yet the bungalow could only embody this novel combination of town and country (and secure the emerging suburban lifestyle) because of the transportation revolution occurring in the first decades of the twentieth century. The scale of this revolution - particularly the advent of the privately owned automobile - would quickly downgrade the vision behind Savage's inspired choice and slowly but steadily alter the look and purpose of suburban housing in new developments. The flair and panache of the bungalow movement in general, and that Savage in particular invested in designing his own home, ultimately affecting building placement, proportioning and the use of natural materials, all went the way of the dodo by the time of the great depression. Exuberance in domestic architecture left town permanently for the more affordable range of dwellings built for aspiring middle class families, replaced by far less elaborate options, much more meagrely appointed, and rendered in cheaper and increasingly more-synthetic materials. Unwittingly, Hubert Savage designed and built an outlier that quickly became an anomaly rather than a representative form. Today it stands as a rare example of a true country bungalow, built on a suburban model that embraces the integration of town and country, sited to draw the best out of its surroundings, and erected just before that model was trumped by the personal automobile.

This post is the second in a series celebrating the centennial of Hubert Savage’s Arts-and-Crafts bungalow, which turned 100 in 2013. Other articles are planned irregularly throughout the year. The ideas are those of David Cubberley (owner since 1988), and speculative to some degree because there is almost no evidence available of Savage family history. The author may be contacted at cubbs@telus.net .

Vestiges of the Interurban line:

|

| On the platform across from City Hall, customers await their departure |

|

| Commemorative sign at Tillicum Station, where the Saanich Interurban began |

|

| Installing tracks to accommodate turns onto Pandora and Douglas |

|

| Model suburb, BCERC, indicating railway involvement in development |

Books for Looks:

The Story of the BC Electric Railway Company, by Henry Ewert, Whitecap Books, 1986.

Victoria's Streetcar Era, by Henry Ewert, Sono Nis Press, 1992.

Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia, by Robert Fishman, Basic Books, 1989.

The City of Los Angeles: History of Transportation, https://usp100la.weebly.com/history-of-transportation.html