"The good building is not one that

hurts the landscape, but one which makes the landscape more beautiful

than it was before the building was built." Frank Lloyd Wright

|

| March 1988, a week after purchasing the Hubert Savage bungalow |

My initial feeling on seeing the house for the first time was relief. A glance towards it from road-level showed an intact front exterior - no obvious signs of dilapidation, no unsympathetic expansions. Just an elegant verandah perched on tapered stone piers, sitting on folds of bedrock, beckoning me to come and take a closer look. Emboldened, I set off to join the gaggle of prospective buyers busy poring over what the ad in Real Estate Victoria called a '1920 character residence.'

|

| A house ensconced in the landscape, rooted to its site with stone |

Four weeks of viewing character homes in Victoria had dampened my optimism about finding one that spoke to me and was rescuable largely with paint and imagination. Many of the places I'd seen had hosted years of hard living, often had long-neglected maintenance needs and, frequently, had been subject to some jarring updatings. There were typically issues to do with services not having been upgraded too. Problems in adapting older character homes to meet new needs often seemed to result in ungainly additions that clashed with original building lines. Awkwardness in the result seemed a frequent fate of these poor structures (inset photo, below right). Thoughts like these closed in

as I made my way up the rising front path, past the smooth folds of exposed bedrock, towards a flight of stone steps set comfortably into the land's contour, before finally reaching that elegant verandah. I thought it was quite special to travel the entire length of the facade before gaining the front door!

It was then mid-March 1988, still sodden here on the island, though not raining that Friday afternoon. I was there attending the first showing of what had apparently been architect Hubert Savage's lifetime home. I hadn't heard of him to that point, but was intrigued to see an architect's handiwork applied to his personal circumstance. Scanning the considerable natural realm between the verandah and the road below, I noted clumps of yellow daffodils poking through carpets of moss and other early spring growth. The house was set well back from the road, on rising ground. A modest parking pad – sufficient for one vehicle only – had been inserted into the landscape, with no sign of a garage.

|

| A few months on, truck on the parking pad, drought firmly in charge |

I crossed the threshold through an open front door that featured a brass lion's-head knocker on a painted plywood panel (clearly not original) and entered a small vestibule containing a clothes closet. There was an original wall sconce with two small bulbs, period wallpaper, and elaborate fir wainscots and plate rails that were stained matte black (I couldn't quite believe that no one had painted it white!). Once inside, impressions flowed in steady succession, sparked by a remarkable complexity of decor. In the kitchen directly ahead, the realtor was offering to guide tours for prospective buyers. To avoid having to share my reactions with a group, I ducked left into the living room, and found myself entirely alone. I preferred to stay aloof anyway, so I could form my own impression of the existing conditions.

|

| Foyer with dark stained wood, original wall sconce |

The living room immediately made a lasting impression. Spacious for a modest house, exuberantly detailed, evidently still mostly original: fir flooring, beamed ceilings, more stained wood panelling and plate rails, a trio of intact windows in a projecting bay, fixed panes of leaded glass in an unusual honeycomb pattern, a large fireplace with asymmetric shelves surrounding it - there was far more to be seen than the eye could readily absorb. Overall the ensemble appeared convincing, as though these particular features all somehow belonged together. Overwhelmed by the sheer abundance of detail, my eyes finally came to rest on a colourful printed frieze band, running along the walls just beneath the ceiling, depicting pastoral scenes from an earlier time. I had never seen anything like it elsewhere: the look of original art imparted a magical quality to the entire room, rendering it utterly atmospheric.

|

| A frieze by Lawson Wood added an atmospheric touch to the living room |

|

| Asymmetric shelving, beamed ceilings, plate rails, matte-black woodwork |

From here I wandered into the dining room, which I also had to myself. Someone had evidently been painting over the darkened wood in a rich cream colour, as there was a ladder and paint tray with brushes and a roller. Although less generously scaled than the living room, it continued the same elaborate decor: another large fireplace, more wainscot and ceiling beams, a pair of original wall-mounted light fixtures, incised shelving, plus a built-in window-seat with leaded glass casements that actually opened.

|

| Original dining room wall sconce, one of a pair |

|

| Incised shelving, high wainscot |

|

| Leaded glass casements |

All this variety was subtly combined in a room of modest proportions, the overall unity marred only by a mock-crystal chandelier someone had felt was necessary to complete the scene. I felt a ripple of excitement at how intact the original decor was thus far, all the while steeling myself for the excesses of renovatory zeal that almost certainly lay ahead.

|

| Leaded glass in fixed panes and casement windows, set into roofed bays |

Next in the sequence of rooms came the kitchen, where I encountered other prospective buyers for the first time. The kitchen seemed open and roomy enough, with three large west-facing windows. A striking room structurally, it ultimately was a disappointment due to some unimaginative renovations that had been imposed on it: a tier of bulky cupboards occupied the end wall, with a counter of

cupboards opposite faced in unfinished wood (run vertically, for a modern touch) and a dirty brown counter top. There were also avocado green and harvest-gold appliances (fad colours from the 1970s that didn't

age well - inset photo, right) detracting from the appeal of what was otherwise a spacious, well-lit country kitchen. The overall shape of the room was intact, as were its patterned ceilings, windows, recessed shelves and much of the original trim. Afternoon light streamed through the ample windows, diminishing the tastelessness of the modern decor to insignificance. I noted that the windows looked directly onto a sheltered garden with mature oaks, centering the building in a natural landscape.

|

| Inset shelving beneath a Tudor arch, kitchen |

My thoughts were interrupted by a couple excitedly imagining how easily the magnificent sash windows I'd just been admiring could be torn out, to accommodate a sliding glass door that would open onto a new deck. Apparently, they hadn't noticed that the kitchen sits virtually at ground level, nor that there was already an elaborate patterned patio just outside the existing rear door. I kept my thoughts to myself however, moving instead to other parts of the house.

|

| Two of those kitchen windows, back at the time of the first restoration |

|

| Elaborate patio pattern viewed from the kitchen |

Venturing into a diminutive central hallway, perhaps fifty square feet all in, I counted seven individual doorways opening off it! Three of these accessed bedrooms, one the sole bathroom, another the attic, one facilitated movement to and from the kitchen itself, while the final one turned out to be a shallow cupboard with shelves the depth of the wall. The central corridor itself was outfitted in grey shag wall-to-wall carpet - clearly the worse for wear - that continued into the bedrooms.

|

| Tiny central corridor with seven door openings |

At the end of this hallway lay the master bedroom. It sported a twin of the trio of sash windows and the fixed-pane leaded glass I had noted in the living room, likewise set into a projecting bay. I tried the sash windows to see if they still worked, which they did. The windows overlooked some mature oaks fringed by blue sky – a real forest, it seemed. Obscuring the top of these windows was a heavy wooden valence with a pull cord, intended to hold

the curtains that once draped the windows (I longed to see this valence gone so the full beauty of those substantial window frames could be revealed). The master bedroom faced east, so would receive morning light during winter months. In the far distance I could just make out the tip of what turned out to be Christmas Hill. The room's overall decor felt in need of a bit of a refresh, but here it truly was a matter of paint and elbow grease. The walls were papered in a large floral pattern (hydrangeas and an unknown flower) that seemed likeable enough. Finding myself alone once more, I discretely lifted a loose corner of the wall-to-wall shag to confirm the presence of intact fir flooring beneath.

The adjoining bedroom, less generous than the main one, was nonetheless still a decent size. Similarly intact, it sloped diagonally towards the far corner. Clearly something had caused the building to settle in that way. Initial feelings of alarm at potential structural flaws gradually subsided as I realized that there were no visible cracks in the floor, walls or ceiling. Whatever had caused the subsidence obviously had happened long ago, and things had not deteriorated further since then. Abstractly, the floor's lack of level recalled somewhat the charm of antique Tudor buildings that have wandered structurally but remain sound after centuries of use. I resumed thinking positively about the room, focusing again on its assets. Among these were windows on two walls, one a generously proportioned sash window facing west with great views to more oaks, another of diamond-paned leaded glass capping a pretty incised shelf. Once again, I was impressed by the ensemble of features.

|

| Fixed-pane leaded glass caps another incised shelf |

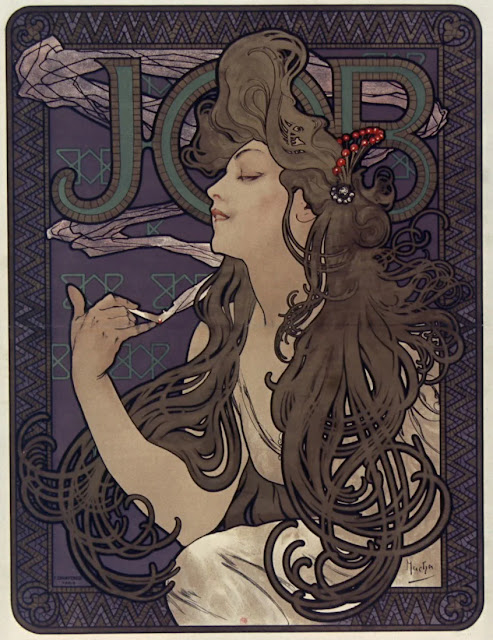

From here I re-entered the central hallway, briefly poking my head through the open door to the attic, an unfinished space accessed via a steep staircase. I could hear people going over it with the realtor, so I opted to move on to the bathroom, which had just been vacated by other potential buyers. I checked my rising enthusiasm in anticipation of this room possibly being a scene of considerable error and excess. This was wise, as the updating couldn't have been more nightmarish. A small room, perhaps five by ten (standard for the era) the entire setup now said do-it-yourself, with fixtures, fittings and overall decor purchased from a budget home centre. It was done up in lamentably poor taste: nondescript vinyl roll-tile flooring, straight-backed prairie-motel-type shower tub with no shower (unfathomable), cultured marble vanity (concrete, surfaced in glossy plastic) with fibreboard cupboards under, unpainted cork-board ceiling tiles, plus a toilet too small to be comfortable for anyone with real legs. The piece de resistance, however, was a vaguely art-nouveau-style wallpaper featuring a repeating image of a woman lounging dreamily while smoking, which (to add to its charm) was vinyl-coated. This all made for a truly hideous muddle. "Oh my!" said a deeply shocked woman's voice from somewhere behind me, upon catching sight of the wallpaper.

|

| Wallpaper after an Alphonse Mucha poster, for effect |

Editing out the chaos of these compounding errors, I searched for positives. One was the original full-size, west-facing window, its trim boards intact, sitting mid-wall above the motel-shower-tub sans shower. Admitting oodles of natural light, it connected to a meadow scene of mature oaks fringed by tall firs. I had caught a version of this scene through the window in the second bedroom, and prior to that, through the kitchen windows. This brought home the realization that on the west side, the house was actually ensconced in a natural meadow in a mature woodland. From the bathroom, you could just make out another dwelling beyond the perimeter, but it was set low enough in the landscape that the eyes were naturally drawn to the fence between the properties. I couldn't help thinking that in spite of all the manifest errors in the bathroom, the tub (were it not straight-backed) was actually well-placed to capture views for a bather.

|

| The neighbouring house that was built on the original grass tennis court |

"The house you see through the window is built on what used to be a grass tennis court before the land was subdivided." The voice was that of the realtor, who had edged into the bog in a quest to appear useful. "The land behind that house is part of Marigold Park, so it will never be developed." I thought she seemed genuine enough but, as I wanted to be alone with my perceptions, I didn't respond to her prompts.

|

| The third bedroom, which has two large windows and two doors |

Across from the bog a third bedroom awaited inspection. Basically a generous square in shape, with a couple of ample windows facing the verandah, the room was light and airy with interesting scenery visible. There was some hideous wallpaper in a forgettable pattern covering the walls, also vinyl-coated. A second doorway opened off this bedroom into the vestibule, which caused me to realize that every room in the house (except for the bog) came with more than one doorway. I realized that, as a result, there was none of the boxy feeling that's typical when smallish rooms have just one door. Also, every room, again apart from the bathroom, came with multiple windows, often on different walls, and usually with real views. The light inside the house was thus exceptional, reinforcing my confidence that real creativity had been exercised in design.

|

| Great light, good views through many windows |

I wanted to be sure to see more of the house, as by this point I was seriously intrigued. I made my way to a long corridor-type room lying just off the kitchen, tucked in under a lifted extension of the main roof line. It wasn't immediately obvious how this room was originally intended to function, but it connected a north-facing glazed door accessing the back garden to a utility area at the south-west end of the house. It came with a barrel-vaulted ceiling (the likes of which I had not seen anywhere) that allowed it to fit under the lifted roof extension. This meant it was a foot or so lower than the other rooms, which appeared to be about eight feet or so high. My eyes came to rest on a bulky washer and dryer set - basically the oversized cubes associated with the modern capacious basement - which occupied the corridor room's length and width substantially. In order to creep these behemoths closer to the electrical panel (I supposed) someone had ripped out what had once been a wall containing the utility closet. This change had not been well done, with little effort made to tidy up the ensuing damage. Scattered bits of this and that were simply left dangling, excavated channels remained bare and open. Overall the room's original purpose seemed unclear, suggesting a need for serious re-imagining: from a pair of cheap aluminum storm windows facing the back garden, to the badly worn floor tile that called out for replacing, to the ripped out utility-closet wall with the dangling bits, to the bare sub-floor exposed in the utility area where the power came in (abandoned plumbing holes open to the crawlspace, a recipe to invite rodents to set up shop) – the entire thing seemed to have been treated as an afterthought. I wasn't sure what to make of the room, but a few of its elements – like the gracefully curved ceiling, the light pouring in from the garden through the windows, and the unusual glazed back door – had distinct charm despite the current disorganized state of affairs. Like the house itself, the room radiated possibility.

|

| Eighteen years later, the utility closet was restored by craftsman Vern Krahn |

Next, I wandered out through the rear door to have a closer look at the building from the outside. The exterior paint was old and faded, though still fairly intact. I didn't love the blue and white combo but felt I could live with it for the time being. There were some missing downspouts, and a section of ancient wood guttering had detached from the fascia. An ugly cat door had been crudely skived into the wall beside the back door. The crawlspace entrance lacked a door and seemed too small to admit a person my size. The roof was evidently ancient too, thick with roofed-over layers of asphalt shingle.

|

| Overgrown foundation plants, ample windows, original terracing, cat door |

In addition, there was a dilapidated shed that had been plunked down in the back garden, with a seat that tilted. So many things obviously needed immediate attention, but as I toted up the pluses and minuses, I was somehow not put off by the building's current condition. My overall impression was in fact strongly positive. There were many assets on offer, beginning with the distinctive originality of the floor plan and the quality of the intact finishing. This was decidedly not a one-size-fits-all sort of house, more a one-of-a-kind house that felt unique. Evidently it had fallen on hard times lately, so there was a lot of deferred maintenance needing to be faced right away. But the structure itself was evidently well-made, with really good bones and a certain design-quirkiness that I responded strongly to. I could feel a potential for renewed greatness. In short, I was optimistic enough about the possibilities to minimize the challenges involved in getting there.

|

| Dilapidated shed, missing downspouts, rampant ivy, pair of stumps |

Back inside, I waited for the realtor to be done with the now-thinning crowd, returning for another look at the living room with the magical frieze. By this point I was certain of wanting to own the characterful Savage house. So when the realtor was free, I took her aside and asked to meet somewhere for the purposes of making an offer. She suggested a nearby restaurant, The Brass Duck, at Tillicum Mall. Over coffee there, I said I was prepared to offer the full asking price, subject to inspection by a qualified building consultant (I also stipulated that the current owner stop all repainting of the dark-stained woodwork, in case their plan included redoing the living room - which, it turned out, it did). Financing the purchase wasn't going to be an issue, as I had a job and significant savings, so was confident of qualifying for a mortgage. The realtor wrote up the offer, which the principals accepted later that evening. Seasoned building inspector Patrick Cutts (by then no spring chicken) crawled around under the building a few days later and his report declared the basic structure sound. It did note the subsidence I'd seen in the second bedroom, attributing it to a large fir root whose parent tree had long ago been removed. He found no other substantive issues, apart from a leaking hot water tank that needed replacement. Once I removed the condition of inspection, the sale completed. In March 1988, I bought a heritage house designed by a local architect for his own family's use. I couldn't have been more pleased!

|

| Post-purchase: ramshackle shed, burn barrel, rampant ivy, ecstatic new owner |

Before visiting Grange Road I had toured quite a few other heritage homes, typically coming away dissatisfied with the existing state of affairs: buildings were rarely oriented for optimal light and often came with too few windows. And typically there were few genuine views available through those windows. Buildings also tended to be placed on smallish lots, gable ends facing the road, in order (presumably) to maximize property yields for developers. Inside, remodelling exercises frequently came at the expense of original character, rendering houses less period-specific, thus more generic and less unique. Many houses were dark inside, a combination of too few windows and the use of dark wood trim. In others the woodwork had been painted over (often with undercoat white) in an effort to brighten things up. Most houses did not have even the beginnings of a garden environment around them. Often they came sited on lots lacking intrinsic character (not that you couldn't have done something with them, rather that it would all have to be invented). Happily, none of these structural limitations applied to the house on Grange Road – in fact, the situation there was exactly the reverse. My inner gardener was as intrigued by an environment I knew intuitively I would never exhaust as my inner designer was by the building's obvious architectural complexity. The lot came with natural contour and a number of mature trees, and it hadn't been mauled by development, so had unique potential for gardening. The building was (to my eye at least) spectacular, alive with light and views, and possessed of genuine aesthetic character. I felt there was unlimited scope for renewal and further development, and I became convinced while looking it over that I should try to secure it. Yes there had been mistakes, some of them quite serious. But no, I wasn't put off, as setting them right was simply the price of admission.

Postscript, September 2023

"Yet impermanence makes house calls wherever we happen to be sitting...it urges us to take nothing for granted, and savour what we can, while we can." Pico Iyer, Globe and Mail, August 26th, 2023

I drafted the notes above shortly after purchasing the Savage bungalow in March 1988. I had an inkling my initial reactions to the place were somehow significant, though I didn't really know why at the time. The notes I made sat in a folder from then until quite recently, when I chanced upon them and realized they offered some fresh perspective on the house. They were a bit incomplete as written, but captured the way the choice to purchase the place unfolded - so I decided to touch them up and am reproducing them now as part of Century Bungalow.

It so happens that thirty five and a half years after purchasing the Savage bungalow on Grange Road, I found myself having recently sold this gem of a house to other people. Hopefully they will be as discerning and respectful in their handling of it we have tried to be. We are now frantically downsizing our household for an imminent move, preparing to inhabit a condo-townhouse that comes with no garden responsibilities. And that's just as well, because I'm getting to an age where the will may still want to tackle the list of chores, but the body is starting to have serious doubts about doing it. I think that all of us reach this point sooner or later in life. However, I remain deeply grateful for the entire experience of living in and managing this significant piece of local heritage. Above all, for the opportunity it gave me to build a compatible garden around it, on a site with unlimited potential. I was lucky to see

|

| Making a new garden, year one |

No comments:

Post a Comment